Born several years before the American Civil War, on August 21, 1854, Frank Andrew Munsey grew up in New England, the son of a rather poor Maine farmer, and, in adolescence and young adulthood, held several occupations, one such being a telegraph operator in an Augusta, Maine hotel. This position in particular allowed him to come into contact with various important members of the era's "movers and shakers." Such meetings, undoubtedly, affected his own opinions on both the nature of success, and his own dreams of fortune.

With very little capital, but with both a drive to succeed and a love of the "by your own bootstraps" tales of Horatio Alger, Jr., Munsey moved to New York City and, in 1882, began publishing, for the most part by himself, a new magazine: The Golden Argosy. Munsey, always one to unabashedly follow the popularity of proven sellers, borrowed part of the name from a successful "boy's literature" magazine popular at the time (and containing authentic Alger stories, no less), Golden Days. Aside from names, Munsey was inspired by the monetary success of other story magazines selling quite well in his home state, such as The People's Literary Companion and Vickery's Fireside Visitor, and sought to produce a magazine affordable to the nation's working-class. For the first years of The Golden Argosy's life, much of the content, fiction and non-fiction alike, was written by Munsey himself; "youth hero" stories, owing more to Alger than bildungsroman formulas, such as "The Boy Broker" (1888) and "Derringforth" (1894) were to be found in The Golden Argosy. One line in particular, from the second volume of "Derringforth," is one that biographer George Britt believed (and I agree) encapsulates perfectly both the type of characters that appeared in the early stories of the Golden Argosy, as well as something of Munsey's own perspective on life and success:

"But the indebtedness before Derringforth was not all. A man of force makes strong friends and strong enemies. To have everybody's friendship is to be a dead level sort of man - a man without individuality, without fire. Derringforth had square corners; had directness. He worked on a straight line. He would rather tunnel a mountain than go around it or over it. Any obstacle smaller than a mountain he felt like forcing aside. These characteristics won the admiration of many and the hatred of those who had to stand aside or smart for their folly."

The ruthlessness Munsey's literary creation displayed on Wall Street was matched only by the pitilessness that Munsey himself demonstrated in the publishing world. After achieving fantastic wealth on the popularity of The Golden Argosy (later truncated, for most of its life, to Argosy) and the later Munsey's Magazine, as well as a successful chain of grocery stories, Munsey plunged headlong into the buying of the great newspapers of the day, envisioning a kind of "journalistic monopoly," such as that of steel under the control of the greatest of his idols, Andrew Carnegie. Munsey was known as a killer in the industry; just as he would do with his many magazines, he would dramatically alter, merge, or end several publications at a time, laying off hundreds of workers if the newspapers were not selling at his desired level. He expected strict discipline from all of his employees, but was rather unpredictable at times; showing kindness by giving gracious severence packages one moment, and the next firing industry mainstays based simply on the fact that they were overweight, or "too old" looking. The Washington Times, The New York Daily News, The New York Sun, The Globe, and a number of other newspaper were purchased by Munsey and either merged with other, more successful papers, or simply done away with. Even the magazine industry, the "bread and butter" of Munsey's career, was not safe from his axe, as the publisher himself was quite proud to point out in a 1903 editorial in Munsey's:

"Not many magazine readers realize that The Argosy, with its quarter century of life, is to-day one of the three oldest magazines of any considerable circulation. The two that antedate it are Harper's and The Century, and in a way, The Argosy is much older than either of those. That is to say, it is older in the blood that flows in its veins, as it absorbed and amalgamated with itself the two oldest magazines in America - Godey's [Lady Book] and Peterson's - both of which were issued in Philadelphia, and which, in their day, occupied an important place in the periodical literature of the country."

Much of Munsey's career followed this path until the end of his days. He became a close acquaintance of Theodore Roosevelt, and was one of two primary financial backers of the former President's "Bull Moose" campaign of 1912. I say acquaintance, as opposed to friend, because, in light of the only comprehensive biography written of the man, George Britt's Forty Years, Forty Millions - The Career of Frank A. Munsey, it seems Munsey did not have many close friends but rather, like Derringforth, always placed business ahead of any personal relationships. He never married, but bequeathed in his will a gracious (for the time) annuity to be paid to a woman who, decades earlier, had spurned his love because she doubted he would amount to very much. Dying in 1925, at the age of 71, Munsey left small percentages of his fortune to a variety of schools and hospitals, with the bulk of his estate going to New York's Metropolitan Museum of Fine Arts. The Argosy, the title that, appropriately enough, had set Munsey on his course, remained in the company's hands until sold to a rival publisher in the early 1940s. By then, however, The Argosy had undergone numerous contextual changes, and no longer resembled the all-fiction weekly that Munsey had produced, nearly single-handedly.

Munsey is remembered as the "father" of the pulp magazine due to the printing process he used in manufacturing The Argosy (following its conversion to an all-fiction periodical in 1896), using the cheapest of pulpwood paper, allowing him to lower the price of his product to 10 cents, at a time when the more "sophisticated" "slicks" (so named for the quality paper their covers were printed on) sold at anywhere between 15 to 30 cents.

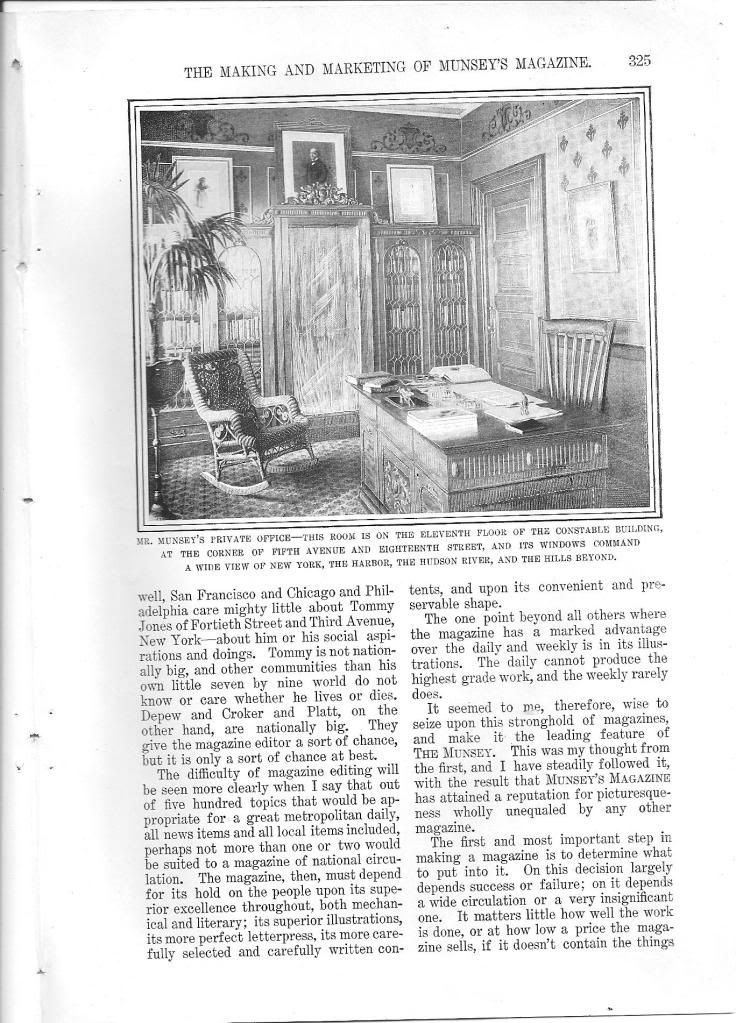

I have posted, along with this introduction to Mr. Munsey, several pages I have scanned from an 1899 issue of Munsey's Magazine, detailing how the magazine was produced, with narration by Munsey himself. Personally, I find the entire process of periodical-production fascinating, especially at the turn of the century, without all of the automation and soullessness that accompanies publishing today. Not that mechanical devices were not utilzied at the time, as evidenced by the images; but rather, there is something about the tangible quality of the work, as opposed to simply pressing a button and letting the machine do it. I realize the irony in my saying something along those lines, while posting on a "blog," but, I have no qualms with admiting that, if given the choice between the printed page and the electronic font, the physical, real item is far superior.

The excerpt I am posting is about 20 pages in all, and I will post the remainder of them in subsequent updates.

Sources:

Britt, George. Forty Years – Forty Millions : The Career of Frank A. Munsey. Port Washington: Kennikat Press, 1972.

Cook, Paul, "Frank Munsey, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and the Rise of the Pulp Era," in A Princess of Mars - Phoenix Science Fiction Classics, by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Rockville: Phoenix Pick, 2009.

Munsey, Frank Andrew. Derringforth- Volume Two. New York: Frank A. Munsey, 1897, 351.

Munsey, Frank Andrew. Derringforth- Volume Two. New York: Frank A. Munsey, 1897, 351.

Munsey, Frank Andrew. "The Story of the Founding of the Munsey Publishing-House," Munsey's Magazine. New York: Frank A. Munsey, Dec. 1907, 417.