There has been a significant gap in posts on my part, I can admit, due mainly to a number of issues beyond my control; although, I always intended for this to be a source of information, as opposed to a constantly updated blog in the more common manner, so a gap in posts is alright, I suppose.

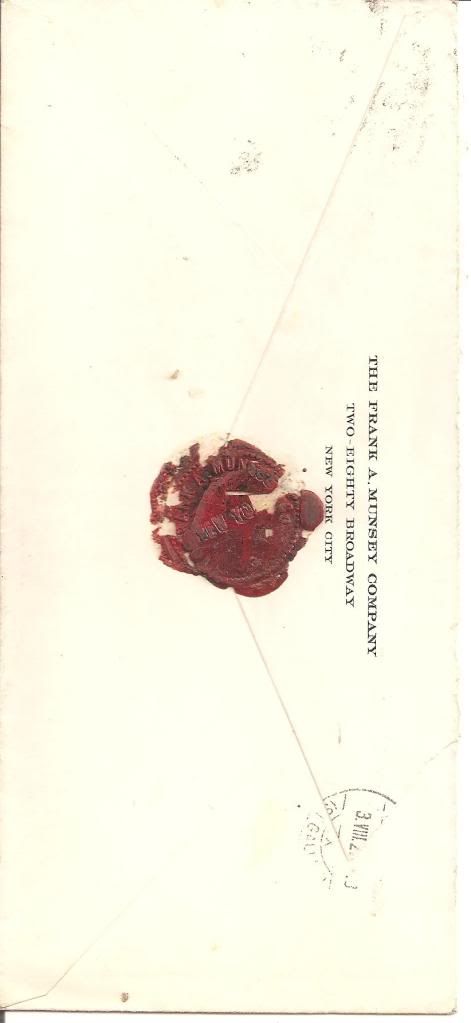

I have been writing a few pulp histories for the Pulp Magazines Project (Argosy and Wonder Stories, in particular), and have been finishing thesis revisions. Recently, I have acquired an immense archive of original, primary source documents relating to the last years of Frank Andrew Munsey's life. I have been combing through these the last month or so, and wanted to post a few on here - I am hoping to expand my biography of Munsey that recently appeared in Blood 'n' Thunder into a larger, more comprehensive work. A few small things at the moment; a letterhead from the Munsey company, a telegraph transcription announcing his death, the cover of a remembrance written by a friend, and other items, with more detailed records appearing in future posts, after I have had adequate time to sort through everything.

Among various letters, transcripts of Munsey's X-ray examinations, and newspaper articles chronicling his health, the items I am most excited about are the three (so far) remembrances concerning Mr. Munsey that are in the archive, all of which I know have never been cited before in any biographical work. These will prove invaluable, not only as primary sources as required by any good biography, but also in the furthering of a point I tried to make in my Blood 'n' Thunder piece; that Munsey was not the horrible, hated monster that he has been portrayed as, almost since the day of his death. The Ebenezer Scrooge-like persona that has filtered down through the decades is one that is unwarranted; primary sources such as those contained in this archive, and others, contradict such an interpretation of the man's life.

Again, what follows is a short sampling of the archive, and I intend to post more substantive items as I go through all of the file's contents. As always, thank you for stopping by!

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Wednesday, September 7, 2011

Dime Novels - The Jeff Clayton series

I am in the process of compiling whatever information possible regarding a series of dime novels (or, in this case, the sub-genre of "thick books") that I have been collecting for quite some time. I first came across the Jeff Clayton series while researching my thesis, and have been fortunate enough to find more copies since.

Inspired by the real-life exploits of the Pinkerton Detective Agency in the late nineteenth century, the dime novel detective was among the most successful of dime novel genres, eventually surpassing the original inexpensive escapism hero, the frontiersman, who had dominated the industry ever since the first dime novel in the 1860s. Jeff Clayton is an excellent example of the quintessential dime novel detective, containing all of the required attributes of such a character. Based in a bustling metropolis, in this case New York City (and often traveling to other locales, from San Francisco to the Orient), Jeff Clayton has the prerequisite detective co-stars; his two assistants - his protégé, Harper Gordon, and the streetwise, uncouth, but undeniably loyal Snoopy Havens. There is also Pong, Clayton's Chinese servant, as well as a collection of other named and unnamed lieutenants who answer Clayton’s call to justice at a moment’s notice. Many of these supporting characters constitute archetypes that would later appear in the pulp hero periodicals, in the form of the assistants and agents that aid in the exploits of Doc Savage, The Shadow, The Spider, and others. Like many dime novel sleuths, Clayton spends a good amount of time explaining to his dumbfounded co-stars the intricate process he uses to arrive at conclusions, similar to the manner in which Holmes feels the need to explain his actions to a confused Watson in Doyle's stories. Clayton battles a menagerie of villains: from local crime-lords, to socialist infiltrators to Chinese tong-men, Clayton’s rogues’ gallery runs the gamut of stock early twentieth century evil-doers.

Inspired by the real-life exploits of the Pinkerton Detective Agency in the late nineteenth century, the dime novel detective was among the most successful of dime novel genres, eventually surpassing the original inexpensive escapism hero, the frontiersman, who had dominated the industry ever since the first dime novel in the 1860s. Jeff Clayton is an excellent example of the quintessential dime novel detective, containing all of the required attributes of such a character. Based in a bustling metropolis, in this case New York City (and often traveling to other locales, from San Francisco to the Orient), Jeff Clayton has the prerequisite detective co-stars; his two assistants - his protégé, Harper Gordon, and the streetwise, uncouth, but undeniably loyal Snoopy Havens. There is also Pong, Clayton's Chinese servant, as well as a collection of other named and unnamed lieutenants who answer Clayton’s call to justice at a moment’s notice. Many of these supporting characters constitute archetypes that would later appear in the pulp hero periodicals, in the form of the assistants and agents that aid in the exploits of Doc Savage, The Shadow, The Spider, and others. Like many dime novel sleuths, Clayton spends a good amount of time explaining to his dumbfounded co-stars the intricate process he uses to arrive at conclusions, similar to the manner in which Holmes feels the need to explain his actions to a confused Watson in Doyle's stories. Clayton battles a menagerie of villains: from local crime-lords, to socialist infiltrators to Chinese tong-men, Clayton’s rogues’ gallery runs the gamut of stock early twentieth century evil-doers.

The series was published by the Arthur Westbrook Company in the decades following the turn of the century, fifty years after Beadles and Adams published the first dime novel. While the Adventure Series of “thick books” in which Clayton appeared ran from 1908 to at least 1928, Clayton’s stories were in publication only between 1910 and 1912, in 34, roughly 300-page novels. The Jeff Clayton stories were all written under the pseudonym of "William Ward," and appeared on an erratic schedule; sometimes monthly, sometimes not. Dime novel fandom tradition considers the Jeff Clayton stories to be rewrites of previous detective fictions; those of Sexton Blake, who appeared in the UK novel series Union Jack, albeit the setting relocated from England to the American eastern seaboard.

My particular interest in Jeff Clayton, aside from its place in American popular literary history, stems from the first issue I read. Jeff Clayton's Fatal Shot (1911) I picked up on a whim, thinking it may help in my graduate work. I was pleased to find, upon finishing the text, that it related to another of my concentrations. The antagonist of the story is attempting to resurrect, what is obviously an allusion to, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, a quasi-Christian movement in late nineteenth century China. The antagonist of the story is working to further the work of “Hung-sew-tsenen,” which, when spoken aloud, sounds a good deal similar to Hung Hsiu-ch'üan (in the Wade-Giles system of Romanization, predominantly in use until the latter half of the twentieth century), or Hong Xiuquan (in the more modern pinyin system). Hong Xiuquan was a scholar who had failed the Qing civil service exams numerous times and who had come to believe that he was in fact the second son of God, younger brother to Jesus, the Taiping Rebellion swept across China, encompassing an impressive amount of land, and even taking the ancient Ming capital of Nanjing (renamed Tianjing, or “Heavenly Capital,” during the Taiping occupation) as its own seat of government. Highly nationalistic, encouraging ethnic Han Chinese to rise against the foreign, Manchurian Qing who had ruled China since the mid-1600s, the Taipings were eventually defeated, due in large part to the aid offered the Qing by Western Powers; the West was fearful of the powerful and modernized state the Taipings threatened to create, as opposed to the weak and subservient Qing, which the West had been able to exploit for quite some time. The Jeff Clayton story, in its relation to the Taipings (50-plus years after the movement's collapse) appealed to me, as I had spent a large amount of time studying the Rebellion; it was the topic of my Senior's Thesis in 2008, and an avenue of research I intend to pursue further in the future. Aside from the use of similar-sounding names, other aspects of the story, such as the antagonist’s lineage and religious convictions, point to the Taipings as obvious inspirations. I also found it interesting that Jeff Clayton happened to battle a gang of Chinese insurgents the very same year that the Qing dynasty collapsed and the Republic of China was formed, following the Xinhai Revolution of 1911. From that issue, I have begun collecting the series wherever I happen to find copies.

The Jeff Clayton series represents all of the attributes, good and bad, of the dime novel detective. He had plenty of time to learn from his progenitors; the series first appeared in 1910, during the days of the dime novel's decline and the pulp magazine’s ascension as America's chief avenue for inexpensive, prose escapism. If a copy can be found, it is well worth the purchase; for either a glimpse into America's literary past, or simply as a good read filled with action and thrills.

Cox, J. Randolph. The Dime Novel Companion: A Source Book. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Thursday, August 25, 2011

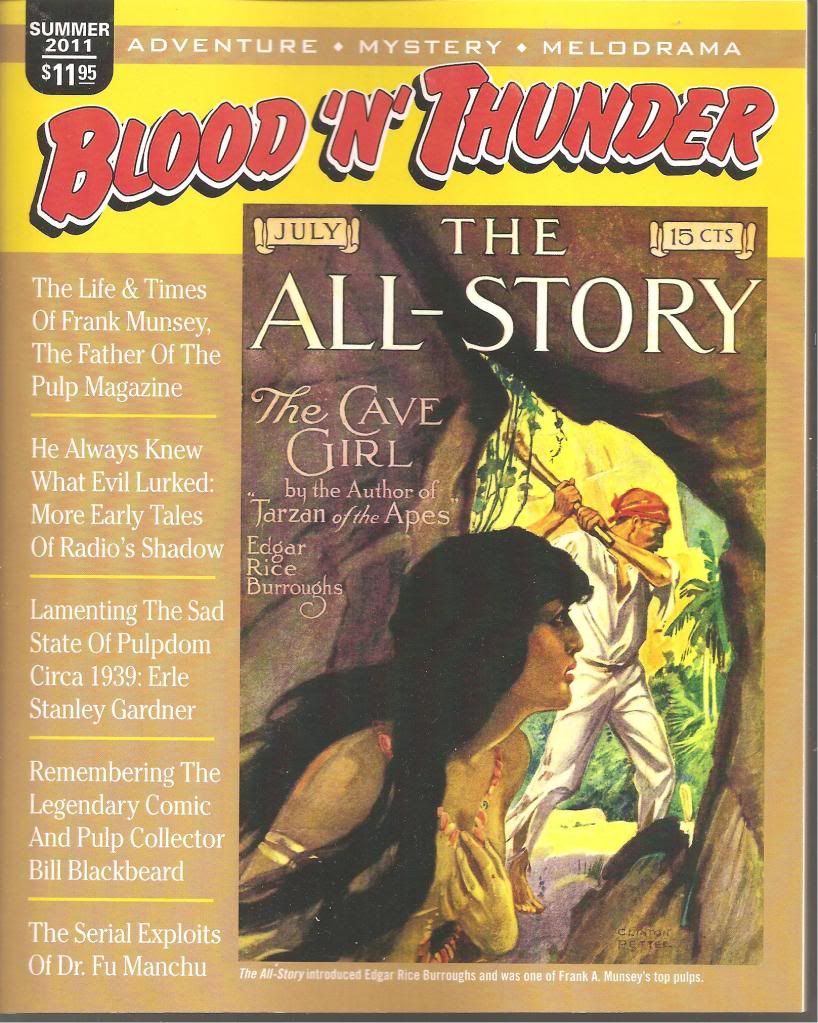

Blood 'n' Thunder - Summer 2011 - Munsey: The Man Who Made The Argosy

While I am waiting for some primary sources to arrive, in relation to an article I am working on concerning dime novels, I just wanted to put up a notice that my expanded (and, in my opinion, much better) biography of Frank Andrew Munsey, founder of the Argosy and creator of the pulp magazine itself, is in print, in the latest issue (Summer 2011) of the pulp journal Blood'n'Thunder, now available at Amazon.

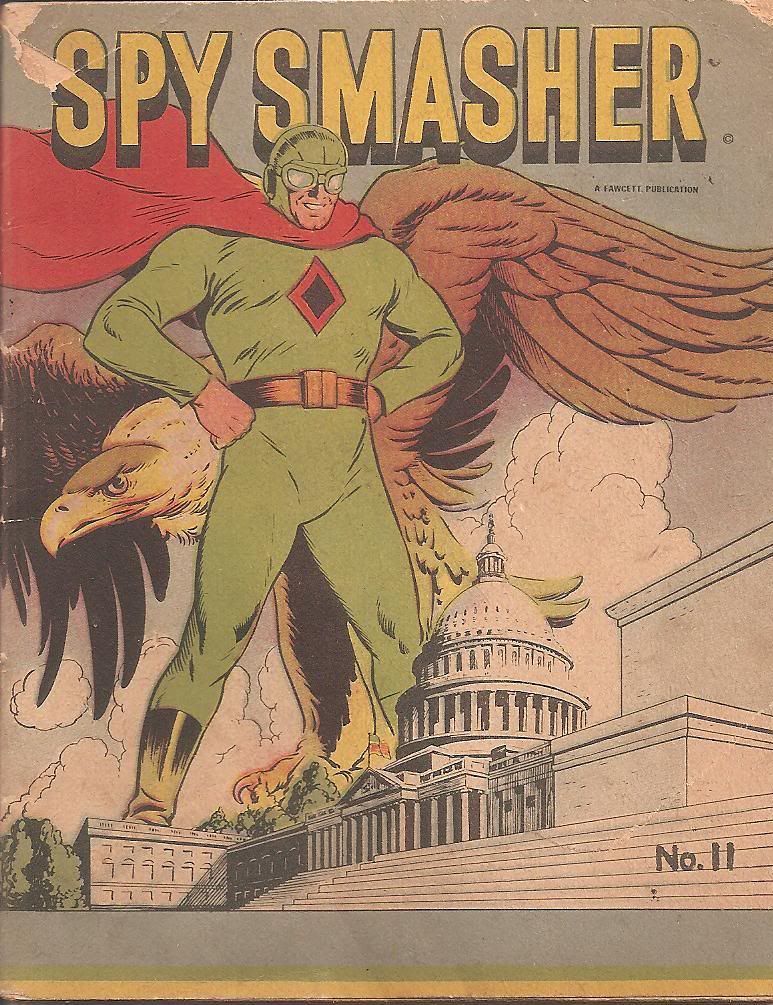

I am very proud of how it turned out, and the images provided by editor Ed Hulse make the piece ten times better than it would have been otherwise. I am in his debt regarding those, as well as the chance to contribute to his journal in the first place. My article is only one of many, and is dwarfed by the other outstanding pieces in the issue, such as: the second installment of Martin Grams Jr.'s study of The Shadow's radio show; Mark Trost's investigation into pulp heroes that transitioned into the four-color world of comics; and an examination of the 1930s serial, The Drums of Fu Manchu, by Daniel J, Neyer; and many others of superior quality to my contribution. Nonetheless, I recommend the issue for all of those interested in pulp and pulp-related history; if you happen to read my article, and enjoy it, please let me know what you thought. Your input, suggestions, and most of all, your readership is sincerely appreciated. Thank you.

I am very proud of how it turned out, and the images provided by editor Ed Hulse make the piece ten times better than it would have been otherwise. I am in his debt regarding those, as well as the chance to contribute to his journal in the first place. My article is only one of many, and is dwarfed by the other outstanding pieces in the issue, such as: the second installment of Martin Grams Jr.'s study of The Shadow's radio show; Mark Trost's investigation into pulp heroes that transitioned into the four-color world of comics; and an examination of the 1930s serial, The Drums of Fu Manchu, by Daniel J, Neyer; and many others of superior quality to my contribution. Nonetheless, I recommend the issue for all of those interested in pulp and pulp-related history; if you happen to read my article, and enjoy it, please let me know what you thought. Your input, suggestions, and most of all, your readership is sincerely appreciated. Thank you.

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

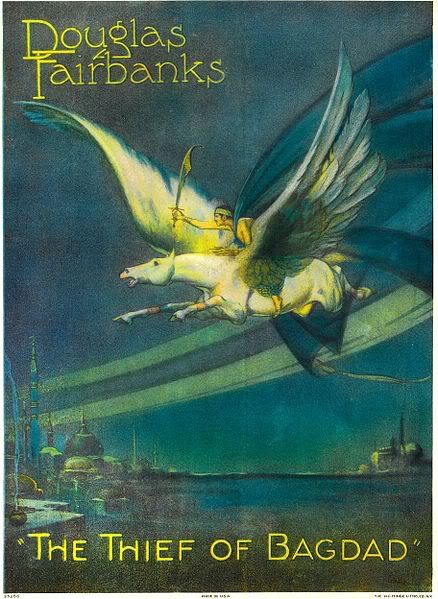

The Thief of Bagdad - 1924 - Douglas Fairbanks

PulpFest 2011 was this past weekend, and while I was unable to attend this time around, I am glad to hear all of the positive reports that have been written the last few days regarding it. It sounds that sales of pulps were good, panels were well-attended, and there were more people attending than in years' prior - all good signs for pulp fandom.

I wanted to post something this time regarding not pulps directly, but rather early cinema. I had seen the 1924, Douglas Fairbanks classic The Thief of Bagdad years earlier, and despite a good deal of the stereotypes and political incorrectness that appears, I still recognized it as an important part of Hollywood, and overall cinematic, history. However, it was only recently that I realized the film's connection to the pulps.

The film's screenplay was written by Alexander Nicholayevitch Romanoff (12 May, 1881 - 12 May, 1945), better known as Achmed Abdullah, a pulp writer who is responsible for dozens upon dozens of stories, voluminous tales that (most often) took place in the "mystic" Orient (generically encompassing anywhere between India, to China to miscellaneous Oceania locales). Appearing in many of the most popular of twentieth century pulp titles, Abdullah's tales were a reflection of his own life, sensationalized accounts inspired by his travels throughout both the Orient and the Occident, and featured glimpses into the languages, religions, customs and cultures he had encountered on those journeys. In addition to his pulp stories, Abdullah penned many novels and books, as well as screenplays for other productions, such as Chang - A Drama of the Wilderness (1927), and the play The Honorable Mr. Wong, which was eventually remade into a film starring the legendary Edward G. Robinson (as a Chinese tong-man in "yellow-face"), and retitled The Hatchet-Man (1932).

Of special note in this film is also one of the earlier screen appearances of Hollywood legend Anna May Wong, one of my favorite actresses and whose biography, Anna May Wong - From Laundryman's Daughter to Hollywood Legend by Graham Russell Hodges, I can not recommend highly enough as providing interesting insight into both her life, as well as the history of early Hollywood and Sino-American relations.

Video courtesy of The Internet Archives - http://www.archive.org

I wanted to post something this time regarding not pulps directly, but rather early cinema. I had seen the 1924, Douglas Fairbanks classic The Thief of Bagdad years earlier, and despite a good deal of the stereotypes and political incorrectness that appears, I still recognized it as an important part of Hollywood, and overall cinematic, history. However, it was only recently that I realized the film's connection to the pulps.

The film's screenplay was written by Alexander Nicholayevitch Romanoff (12 May, 1881 - 12 May, 1945), better known as Achmed Abdullah, a pulp writer who is responsible for dozens upon dozens of stories, voluminous tales that (most often) took place in the "mystic" Orient (generically encompassing anywhere between India, to China to miscellaneous Oceania locales). Appearing in many of the most popular of twentieth century pulp titles, Abdullah's tales were a reflection of his own life, sensationalized accounts inspired by his travels throughout both the Orient and the Occident, and featured glimpses into the languages, religions, customs and cultures he had encountered on those journeys. In addition to his pulp stories, Abdullah penned many novels and books, as well as screenplays for other productions, such as Chang - A Drama of the Wilderness (1927), and the play The Honorable Mr. Wong, which was eventually remade into a film starring the legendary Edward G. Robinson (as a Chinese tong-man in "yellow-face"), and retitled The Hatchet-Man (1932).

Of special note in this film is also one of the earlier screen appearances of Hollywood legend Anna May Wong, one of my favorite actresses and whose biography, Anna May Wong - From Laundryman's Daughter to Hollywood Legend by Graham Russell Hodges, I can not recommend highly enough as providing interesting insight into both her life, as well as the history of early Hollywood and Sino-American relations.

Video courtesy of The Internet Archives - http://www.archive.org

Saturday, July 23, 2011

Original Fandom - Golden Age Green Lantern

A good friend of mine sent this to me the other day, and I just wanted to post it here as well, as it speaks a great deal about the history of fandom, comic books, and just the simple idea that kids, at one point, were able to have fun without "Xstations," "PlayBoxes," "I-Everythings," and whatever manner of de-individualizing nonsense is all the rage these days. And, before I am accused of being an "old fogey;" I am 28 years old - then again, maybe that is an old fogey, these days.

Image courtesy of Awesome Robo.

http://www.awesome-robo.com/2011/06/green-lantern-makes-for-amazing-costume.html

Image courtesy of Awesome Robo.

http://www.awesome-robo.com/2011/06/green-lantern-makes-for-amazing-costume.html

Sunday, July 10, 2011

Dime Novels and Story Papers III - A Brief Commentary

The story papers, often combined in recent writings with other works of the period to form the somewhat problematic and generic term of "Dime Novels," actually have a history all their own, quite separate, but still related to, the history of dime novels. The story papers are also intertwined with the history of the pulp magazines, as the first all-fiction pulp magazine, Frank Munsey's The Argosy, began life as a story paper of juvenile fiction, first published in December of 1882. One of the most prolific pulp publishers, the Street and Smith Company, also has its origins in the story paper era. Depending on how one looks at the situation, whether the dime novel or the story paper came first could be debated; some will say that the story paper, as it reached its heights of popularity in the late nineteenth century, only did so due to the popularity of dime novels. Others will contend that the early story papers, and the newspaper fiction columns that preceded them, helped “popularize literature,” and paved the way for the growth of dime novels following the release of Beadle and Adam's first dime novel, Malaeska, The Indian Wife of the White Hunter (by Ann S. Stephens) in 1860. I have heard both arguments, from those who favor one medium over the other. Whatever the case, the popularity these two mediums enjoyed is unquestionable, and many aspiring publishing-magnates realized this fact. In Munsey's case, The Golden Argosy's title was partly borrowed from another juvenile fiction paper popular at the time, Golden Days, which featured the works of many writers who would later work for Munsey, such as Edward S. Ellis and Horatio Alger, Jr.

Aside from the name of his paper, Munsey was inspired by the monetary success of other story papers selling quite well back in his home state of Maine, such as The People's Literary Companion and Vickery's Fireside Visitor. There was a rise in literacy that began during the mid-nineteenth century, thanks to both the spread of public education, as well as the Post Office Act of 1852; this Act allowed for the publisher to ship reading material for two cents, as opposed to the previous six cents the recipient was responsible for paying upon delivery. This change in postal rates has been called “the greatest boon to mass education ever conceived” – more people were reading, and finding pleasure in doing so, than at any other time in history previously. Beginning with serialized stories printed in newspapers such as The New York Ledger (beginning in 1856), helmed by Richard Bonner (“The Barnum of the publishing industry”), popular fiction eventually began to sell on its own, and became an industry outside of the newspapers.

Two youths who were avid readers of Bonner’s Ledger were Francis Scott Street and Francis Shubael Smith, business manager and editor, respectively, on a small-circulation newspaper, The Sunday Dispatch. The owner of the paper, one Amos Williams (who, by all accounts, held a strong, personal connection to the two) eventually sold The Dispatch, now re-titled The New York Weekly Dispatch, to Street and Smith; on the tenth of October, 1857, Smith’s serial “The Vestmaker’s Apprentice; Or, The Vampryes of Society” appeared in the Weekly, and circulation immediately shot upward for what had been, until that time, a struggling publication. Smith continued writing short stories and serials for the paper, while Street’s business acumen aided in the Weekly’s rise; foreseeing the economic panic that gripped the nation in 1857, he (smartly) began to focus on the selling of papers at newsstands, as opposed to relying on subscriptions. This move kept The New York Weekly (Dispatch having been dropped within a year of Smith’s first story) not only afloat during the panic, but actually prosperous. One of the early progenitors of the story papers that would flood the market in the succeeding years had been born. Other publications and periodicals followed, with the Street and Smith Company growing to become a powerful force in the American publishing industry throughout most of the twentieth century. It was their example, in addition to those of such “captains of industry” as Andrew Carnegie and J. Pierpont Morgan, that inspired a young Frank Munsey to seek his fortunes outside of the confines of a small, telegraph office in Maine. A little over twelve years after emulating Street and Smith’s success with the story papers, Munsey would (directly or indirectly – it depends on one’s personal opinion of Munsey) kill off the medium, or at the very least, speed its demise, with the introduction of the pulp magazine.

The story papers did not necessarily replace dime novels as popular literature, or vice versa, such as comic books would do to pulps in the following century; rather, one complimented the other, both featuring a secondary route to inexpensive, working-class literature. In many cases, some of the same stories, or variations of which, appeared in both mediums. Detective Nick Carter, collegiate hero Frank Merriwell, and a host of others appeared in both dime novels and story papers. Dime novels eventually died out, only to be followed by the story papers; by the 1920s, story papers still circulated, but these were very few in number, the last remnants that existed before becoming overrun by the pulp magazine, which was able to offer hundreds of pages of sensationalized fiction.

As has been said, works such as The Nugget Library and The Golden Argosy were the precursors to pulp magazines, and later comic books. While having different audiences to a large degree, the place of inexpensive, working-class literature was filled by the dime novels and papers, to be succeeded by the pulps and then comic books. As was the case with the pulp magazines later, the dime novels and story papers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were derided as garbage by overseers of the "hoi polloi," who warned that they corrupted youths' minds. Voices, of which the likes of Frederic Wertham and others would be an echo of decades later, claimed that the fantasy found within those pages created a lawless and lustful generation of young Americans. As would also be the case years later, the authors of such stories were called hacks, and their understanding of literary standards repeatedly called into question. As dime novel historian Edmund Pearson pointed out in 1922, however, such attacks probably had less to do with concerns over morality and more to do with book publisher's threatened sales. In speaking of a recently-donated collection of dime novels to the New York Public Library, Pearson writes:

It is perpetually useful for each generation to see how much unnecessary anguish has been suffered in the past over things which were really harmless . . .They were never immoral; on the contrary, they reeked of morality. . . Indeed, there is reason to believe that many of the superstitious beliefs about the harmfulness of the dime novel were eagerly fostered and circulated by agents of the "respectable" publishing houses, to whom any books which sold for ten cents was grossly immoral, for that very reason.

Anyone who actually reads dime novels and story papers will see exactly what Pearson is speaking of; the level of traditional, Puritanical morality evident in the majority of such works is extremely high. Consider, for example, Street and Smith’s understanding of what was fit to print in their papers:

They [other periodicals and story papers of the day] will discover, when it is too late, perhaps, that the people of the United States will not sustain papers whose editors gather up all the filth from the gutters and dens of infamy to make their columns “spicy.” A paper, to obtain a permanent circulation, must inculcate good morals and pay some regard to decency.

While this does not discount the presence of other attributes understood to be unacceptable today (such as instances of nativism, or misogyny), it does provide significant argument against the notion that the popular literature was poisoning youngsters' minds with delusions of sin, vice, promiscuity, and other similar accusations.

On a slight, opinionated aside, it is interesting to note the progression of popular literature, from the dime novels up through the comic books and then….to what? Comic books still exist, but that is really a niche audience, that does not grow a great deal no matter what marketing gimmicks movie studios try to use in promoting comic book-based films. As far as predominant, inexpensive literature; what has, or could, replace the comic book? In my mind, nothing really, brought on by my opinion that the majority of Americans do not actually read (the pseudo-intellectual hipster sitting around sipping a mocha with a stack of books on his or her table at Barnes and Noble does not count as “reading”); also, the closest contender (today's paperback novels) are not nearly as inexpensive as comics and pulps were, by comparisons that take inflation into account. I can not imagine there will ever be anything that will fill the void left, first by the story papers and dime novels, and later by the pulps, in terms of actual, physical works, but also in the diversity of stories, characters, and ideas that flourished in the pages of those mediums. The creativity of those days is lacking today, and I sincerely have my doubts concerning whether it will, or even can, be reclaimed.

Ron Goulart, Cheap Thrills - An Informal History of the Pulp Magazines (New York: Arlington House, 1972).

Edmund Pearson, Dime Novels; Or, Following an Old Trail in Popular Literature (Port Washington: Kennikat Press, 1968 [Little, Brown and Company, 1929]).

Edmund Pearson, "Beadle's Dime Novels," The Independent, August 5, 1922, 37.

Quentin Reynolds, The Fiction Factory, or from Pulp Row to Quality Street – The Story of 100 Years of Publishing at Street and Smith (New York: Random House, 1955).

Thank you to the Galactic Central webpage cover gallery for the Golden Argosy image.

Thank you to the Galactic Central webpage cover gallery for the Golden Argosy image.

Tuesday, June 28, 2011

Dime Novels and Story Papers - II

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

Dime Novels and Story Papers

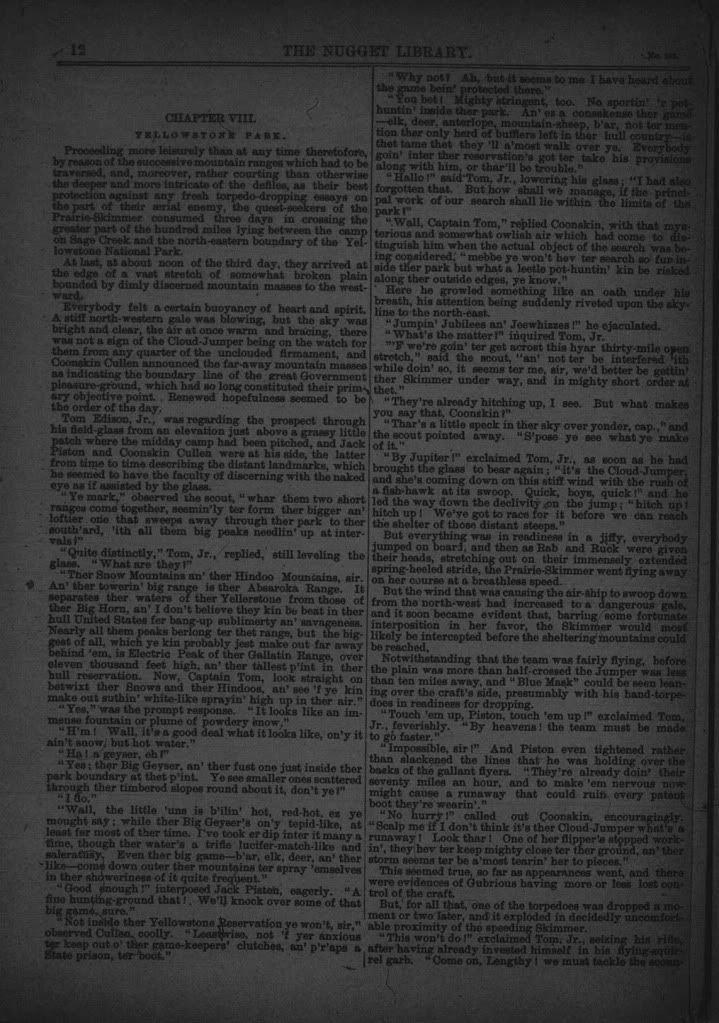

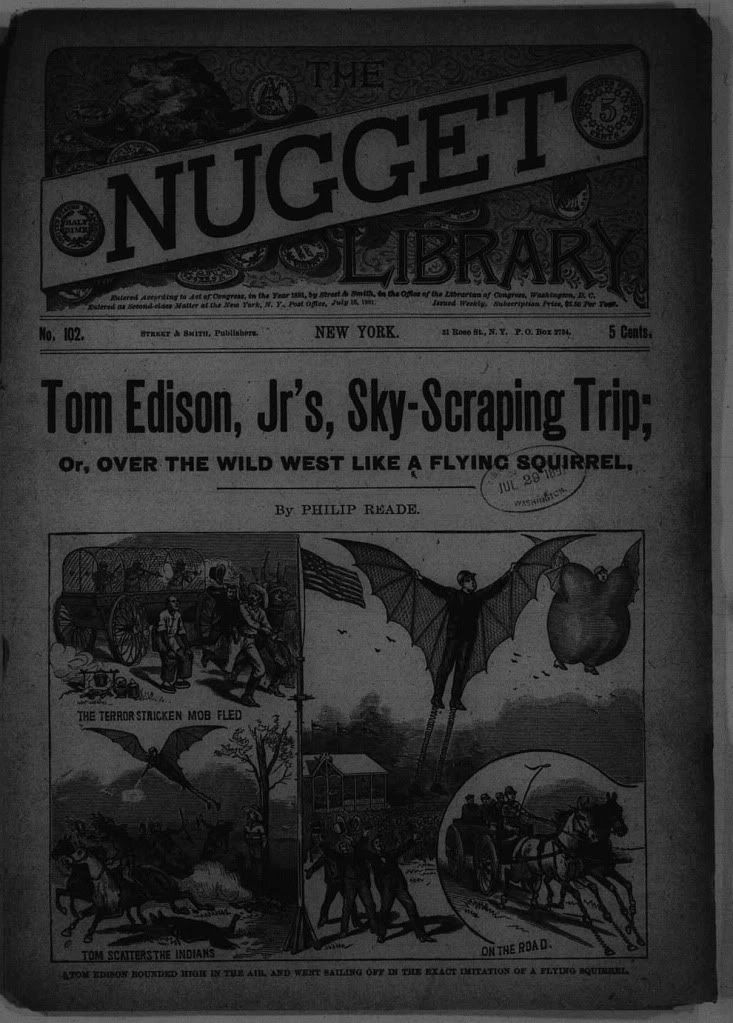

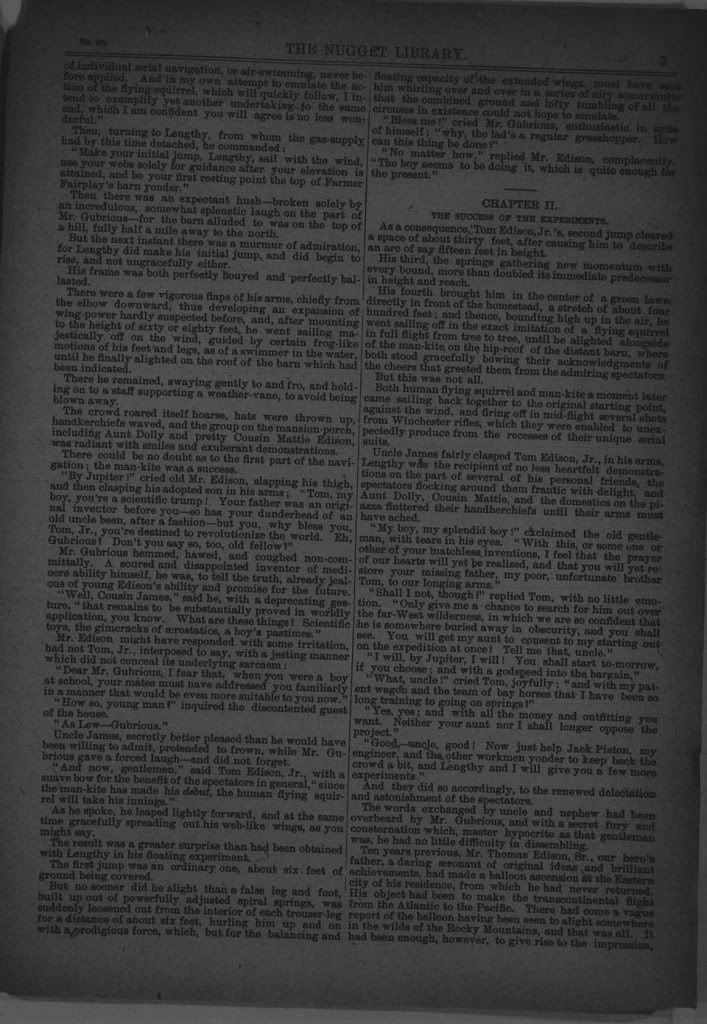

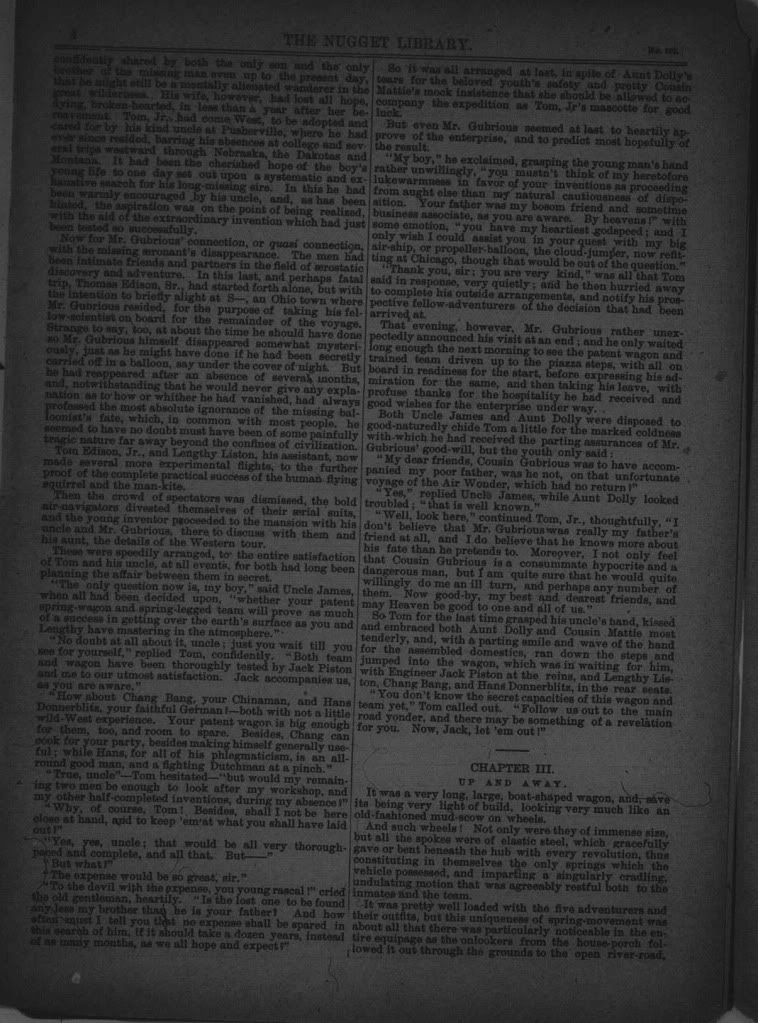

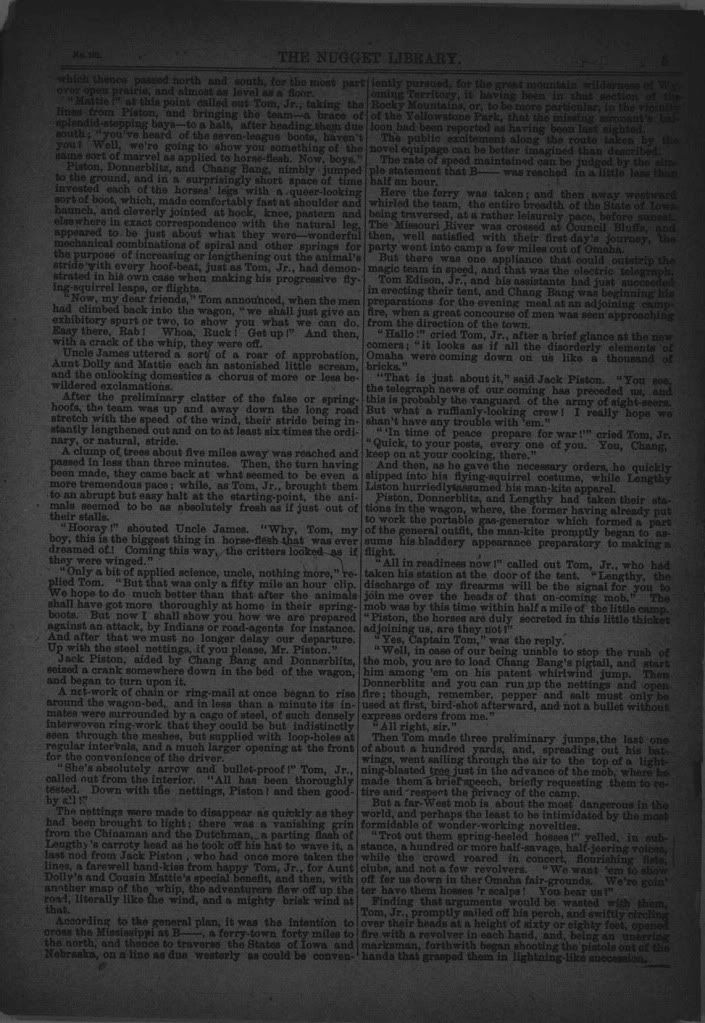

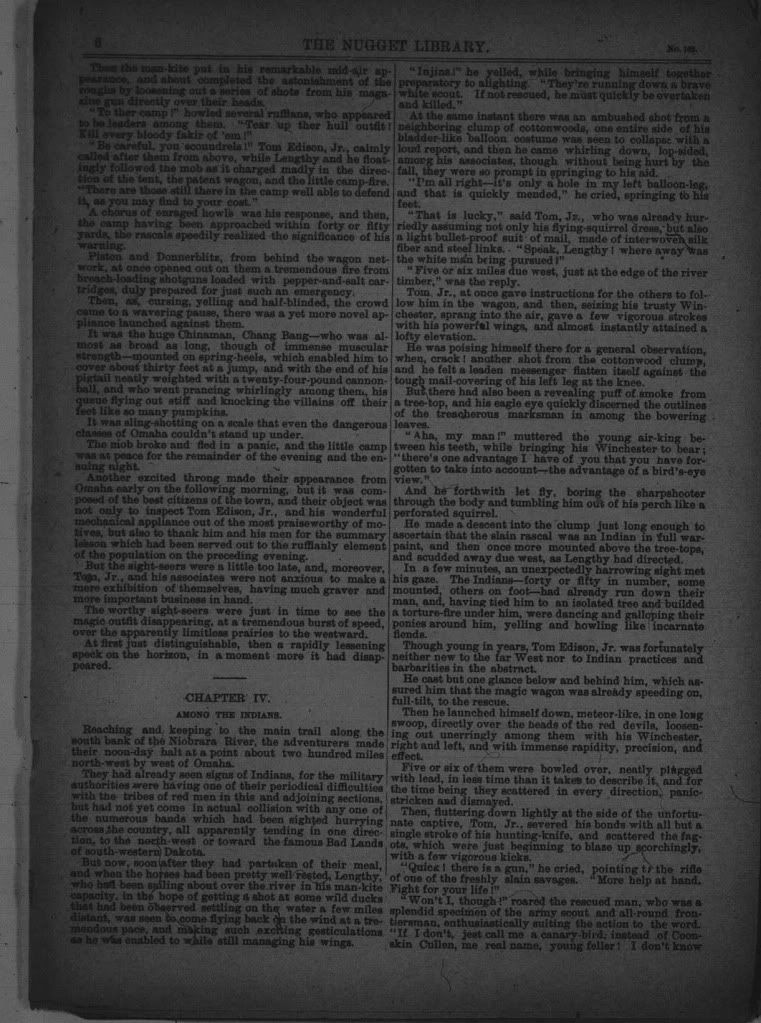

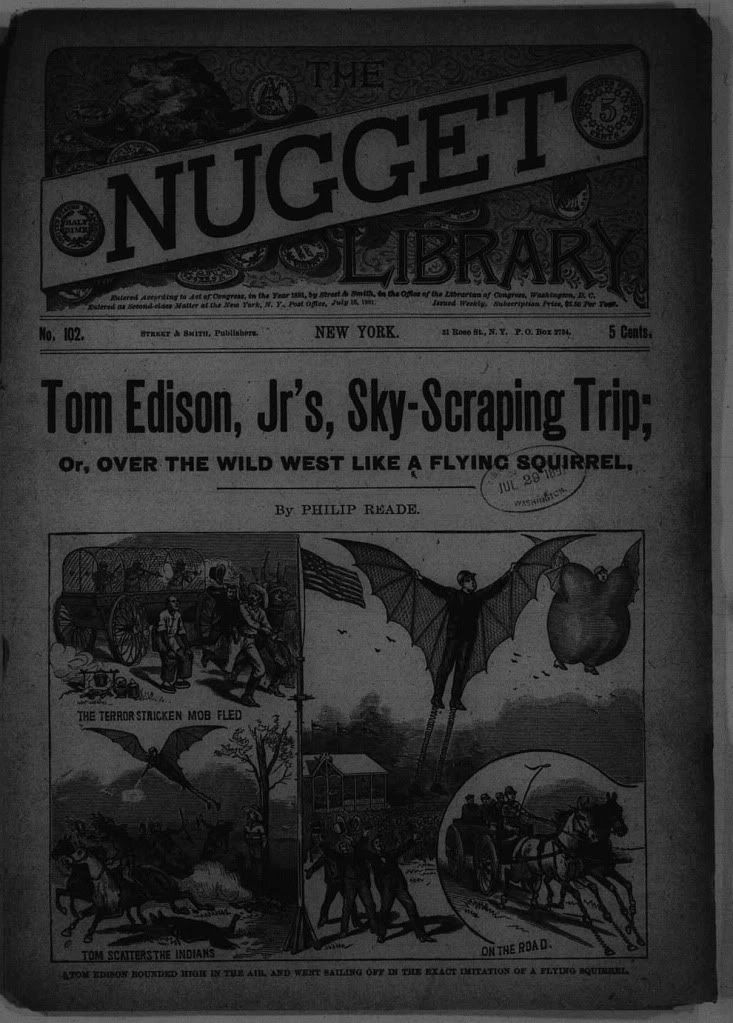

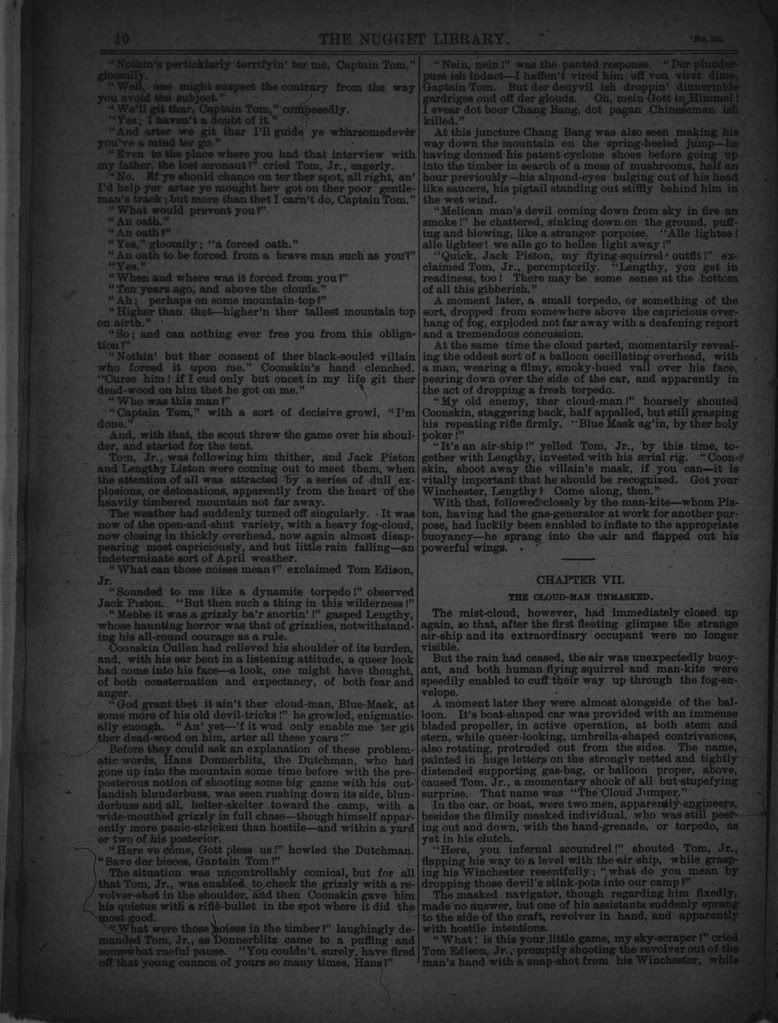

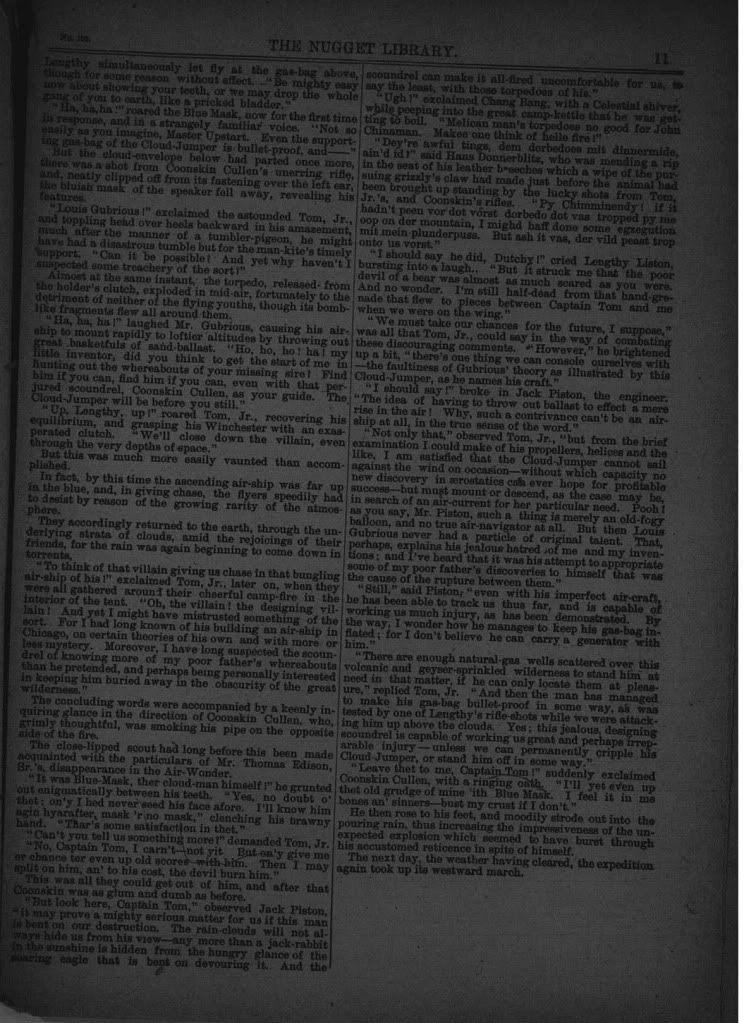

While revising my Master's Thesis for publication, I wrote a short bit about a rather small genre of fiction that appeared in the story papers of the late nineteenth century, that of the "Edisonade." The term popularized by John Clute in the pages of his Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, these stories were boy-adventure tales. Unlike the "up by your own bootstraps" tales written by the likes of Horatio Alger, Jr., these stories featured a young boy who is either a relative of famed inventor Thomas Alva Edison, or someone claiming him as a namesake. The boy inventor often devises some mechanical creation in order to thwart an enemy, villains that ranged from "yellow peril" Fu-Manchu prototypes, to pirates, to international criminal masterminds.

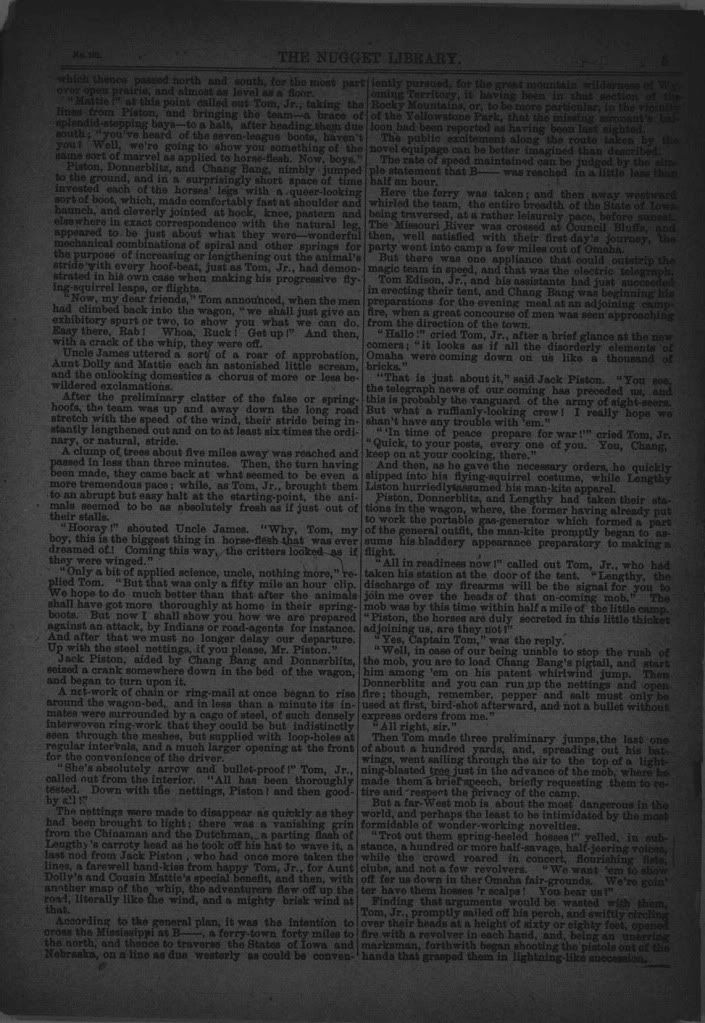

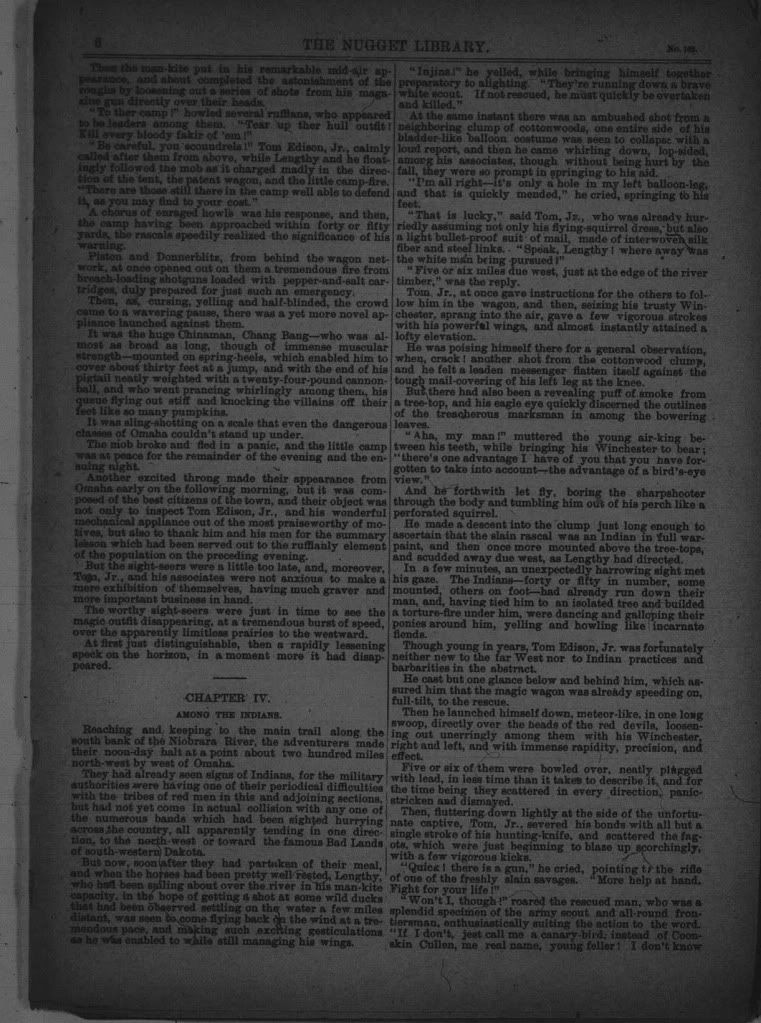

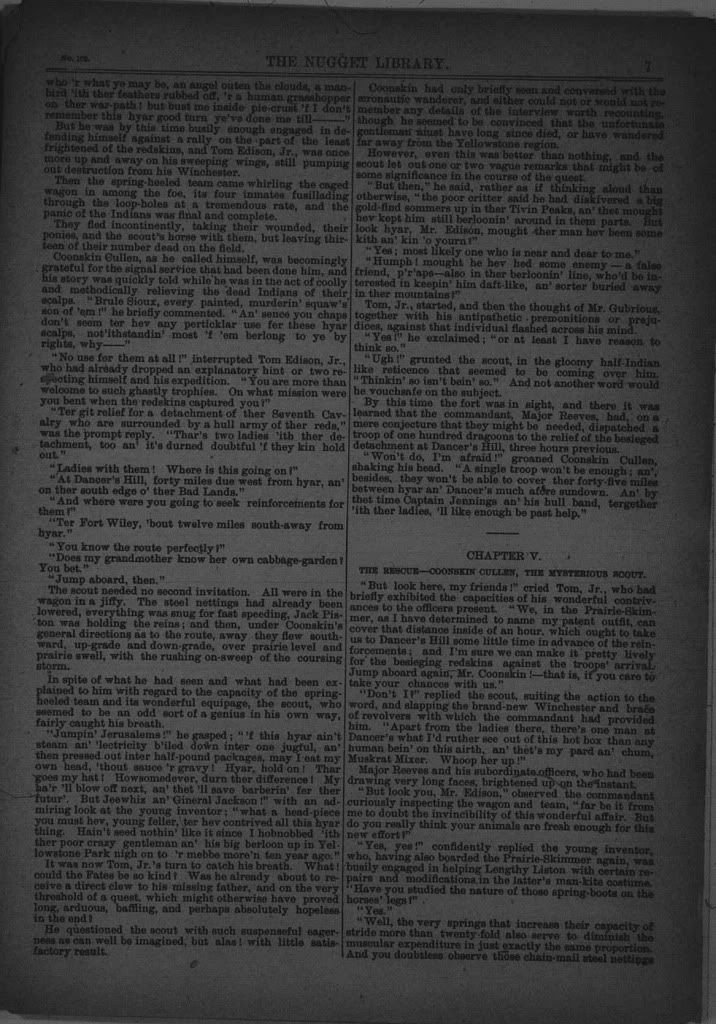

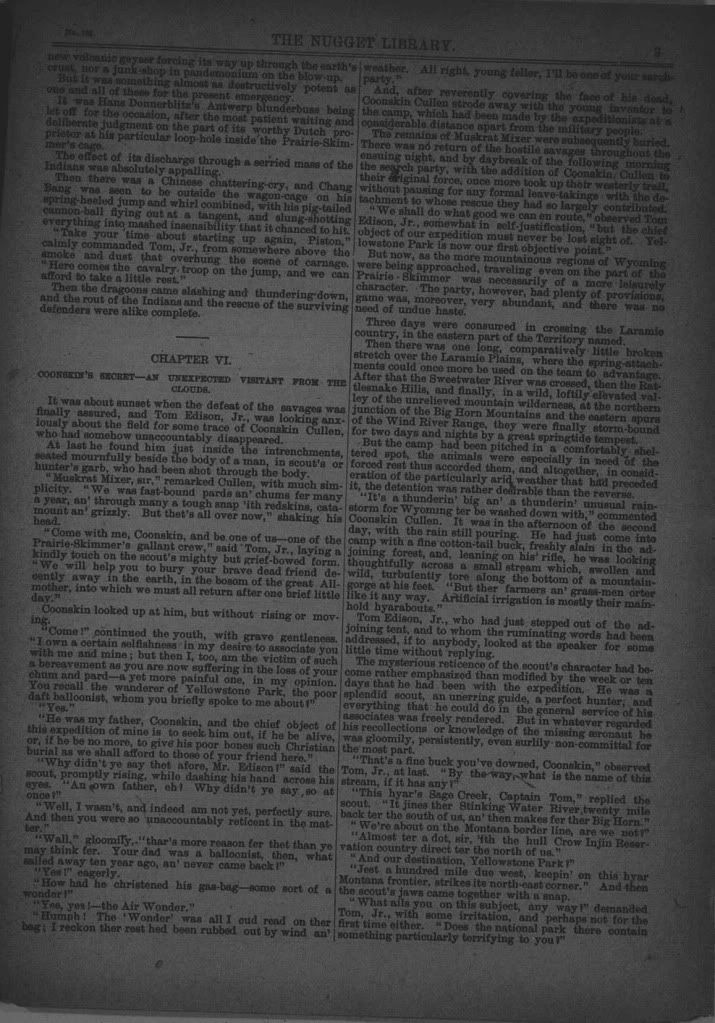

I have posted scans of issue 102 of the late nineteenth century story paper The Nugget Library, and its feature story "Tom Edison, Jr.'s Sky-Scraping Trip," by Philip Reade from 1891. I find such works important because they are truly the precursors to every sort of working-class literature to have followed, from pulp magazines to comic books, and more. Such works do not usually involve the most convoluted plots, and are not prime examples of political correctness. Many of the dime novel and story paper stories, such as the following, feature racial stereotypes not tolerated today; be warned, this particular issue contains stereotypes of Chinese characters, among others. However, it is my view that these should be taken for what they are, products of their time, and any attempts to place twenty-first century values on nineteenth century works is not the proper avenue in which to pursue historical inquiries. It is unfortunate, but it is what it is and it is still a part of our history, for better or for worse.

I believe I will write some more on the history of such ephemera; however, for the meantime, I submit these pages. They are digital scans of microfilm reels available at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. A search of their online catalog will present them, and the staff of the Microform Reading Rooms (1st Floor, The Jefferson Building) are always helpful and a pleasure to deal with. I can not say the same for other rooms, but the Microfilm department has always been superb to work with.

www.loc.gov - Library of Congress Main Site

http://www.loc.gov/rr/microform/ - Library of Congress Microform Reading Rooms Site

To Be Concluded

I have posted scans of issue 102 of the late nineteenth century story paper The Nugget Library, and its feature story "Tom Edison, Jr.'s Sky-Scraping Trip," by Philip Reade from 1891. I find such works important because they are truly the precursors to every sort of working-class literature to have followed, from pulp magazines to comic books, and more. Such works do not usually involve the most convoluted plots, and are not prime examples of political correctness. Many of the dime novel and story paper stories, such as the following, feature racial stereotypes not tolerated today; be warned, this particular issue contains stereotypes of Chinese characters, among others. However, it is my view that these should be taken for what they are, products of their time, and any attempts to place twenty-first century values on nineteenth century works is not the proper avenue in which to pursue historical inquiries. It is unfortunate, but it is what it is and it is still a part of our history, for better or for worse.

I believe I will write some more on the history of such ephemera; however, for the meantime, I submit these pages. They are digital scans of microfilm reels available at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. A search of their online catalog will present them, and the staff of the Microform Reading Rooms (1st Floor, The Jefferson Building) are always helpful and a pleasure to deal with. I can not say the same for other rooms, but the Microfilm department has always been superb to work with.

www.loc.gov - Library of Congress Main Site

http://www.loc.gov/rr/microform/ - Library of Congress Microform Reading Rooms Site

To Be Concluded

Monday, May 30, 2011

Memorial Day

In recognition of Memorial Day, I did not want to write a great deal, as not much writing is needed; we all know why this holiday, more than most that occur throughout the year, is important and should be recognized. I decided on a small post, a short show of some of my favorite war-era covers from my personal collection of early twentieth century escapism, the stuff we on the home-front are fortunate enough to have the leisure of reading and enjoying, while Our Boys are overseas, sacrificing blood and limbs, and (as Memorial Day reminds us) often times a great deal more, whether it's the First World War or the Second, the Korean War or all of the other sites of the so-called "Cold War", and beyond.

From 1776 to Vietnam and up through the present, I sincerely thank you for all you have done, to those who have given their all.

From 1776 to Vietnam and up through the present, I sincerely thank you for all you have done, to those who have given their all.

Saturday, May 21, 2011

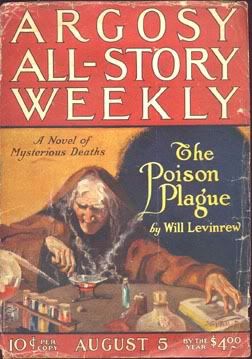

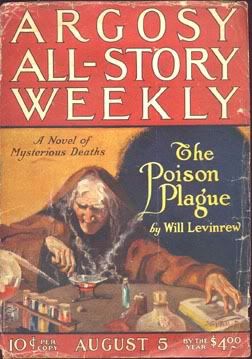

The Argosy All-Story Weekly - August 5, 1922

It certainly has been a busy month for me, which, unfortunately has led to updates not being as often as I would like. I have recently taken on archival work at my hometown's historical society, in addition to the historiographical work I do already. I also have been doing additional research into Frank Munsey's life, as a greatly-expanded revision of my previous entries concerning him are slated for publication collectively later this summer. I hope such delays do not become a habit on my part.

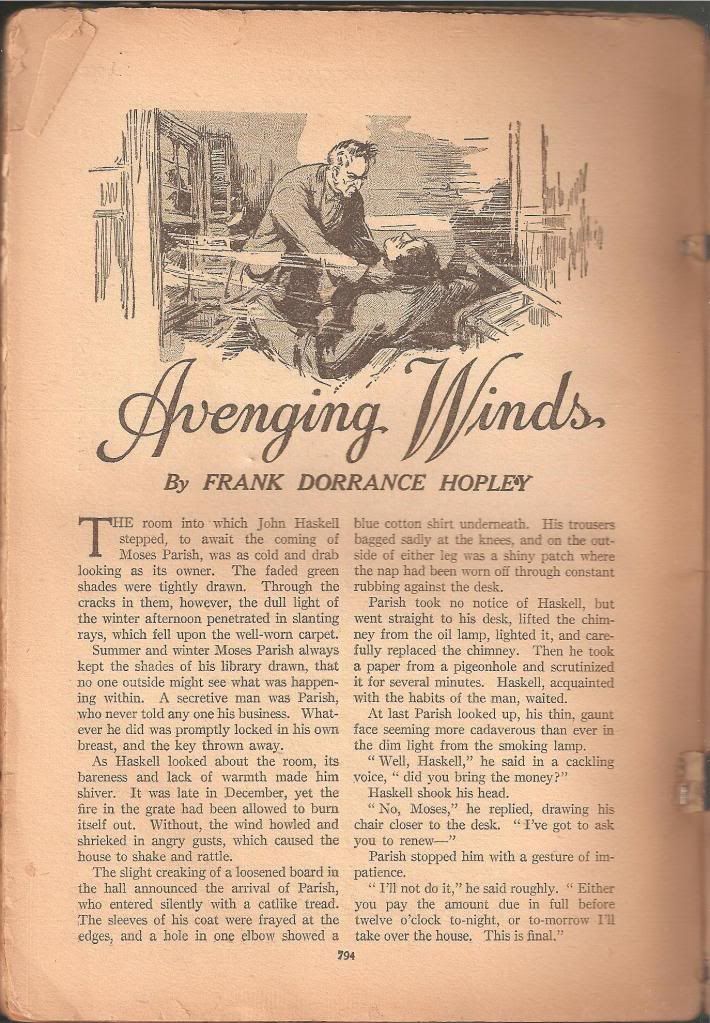

I wanted to post something of a personal nature; a story from the first pulp I ever acquired. It was something I picked up years and years ago, in a "$1 bin" at an antique store I visited while on a trip. Something about it interested me, and I picked it up out of curiosity more than anything; curiosity concerning this item that seemed to me in my ignorance, to be nothing more than an old manner of comic book. The stories inside I found interesting, and enjoyable to read, but I have to say I never gave pulp collecting much thought until years later, when I began collecting pulps that were the first to feature Howard Phillips Lovecraft's stories, and then expanded my interest into other authors and genres.

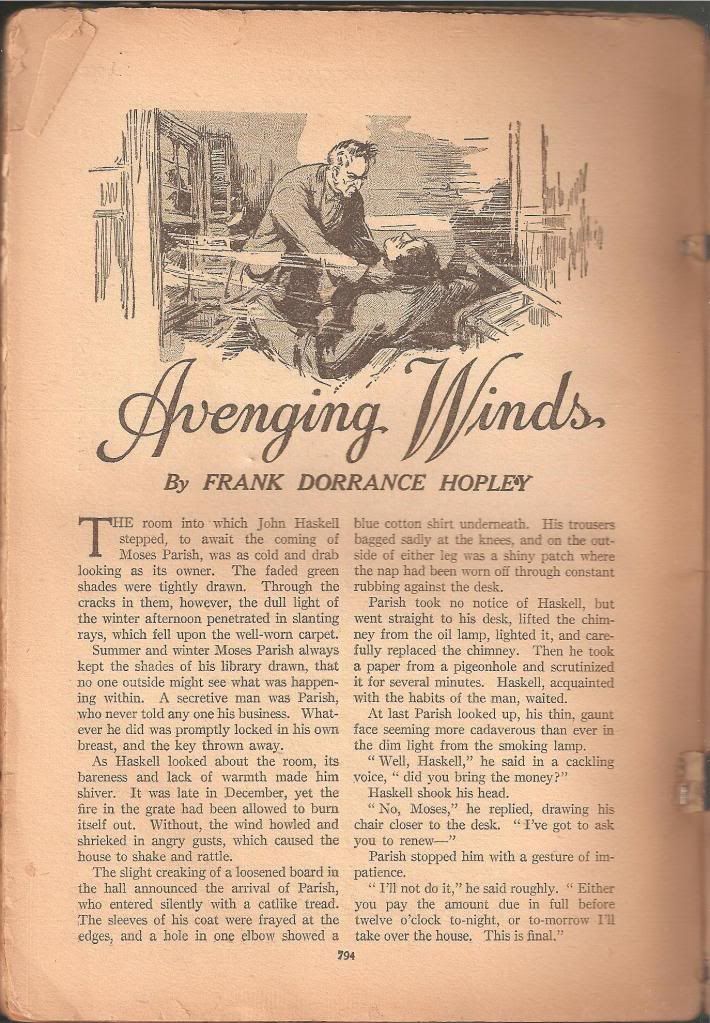

I have scanned a short story from that first issue, appearing near the end of the magazine and being a simple "mystery-revenge" plot, nothing extraordinary but still, in my mind, enjoyable and a good representative of the sort of short stories to be found in pulpish ephemera.

Thanks to the Galactic Central website's index of pulp covers, as the cover to my copy detached years ago.

I wanted to post something of a personal nature; a story from the first pulp I ever acquired. It was something I picked up years and years ago, in a "$1 bin" at an antique store I visited while on a trip. Something about it interested me, and I picked it up out of curiosity more than anything; curiosity concerning this item that seemed to me in my ignorance, to be nothing more than an old manner of comic book. The stories inside I found interesting, and enjoyable to read, but I have to say I never gave pulp collecting much thought until years later, when I began collecting pulps that were the first to feature Howard Phillips Lovecraft's stories, and then expanded my interest into other authors and genres.

I have scanned a short story from that first issue, appearing near the end of the magazine and being a simple "mystery-revenge" plot, nothing extraordinary but still, in my mind, enjoyable and a good representative of the sort of short stories to be found in pulpish ephemera.

Thanks to the Galactic Central website's index of pulp covers, as the cover to my copy detached years ago.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)