|

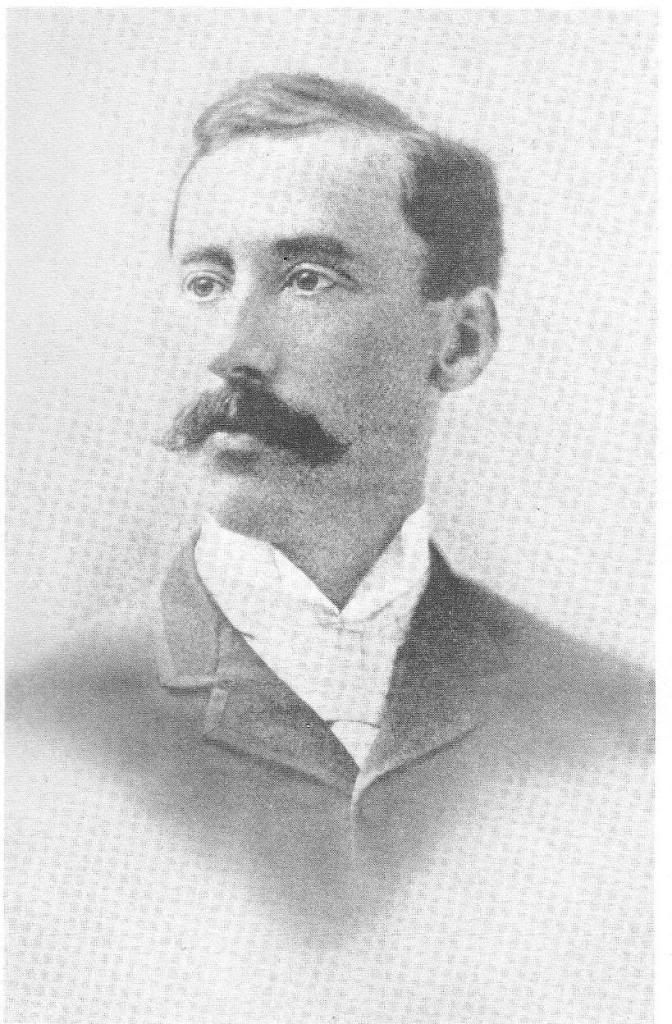

| Munsey, in 1896 |

|

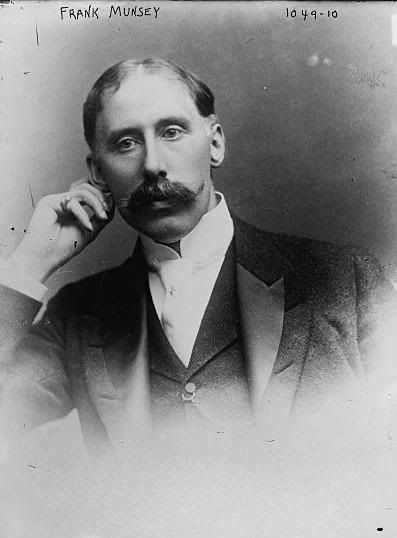

| Munsey, 1910 |

|

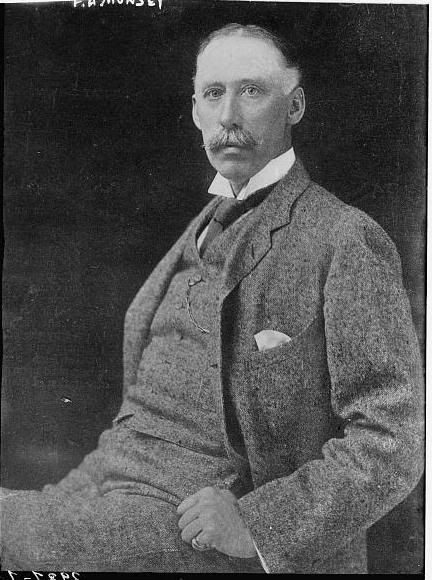

| Munsey, ca. 1915 (probably later) |

Even before the Republican convention, Munsey had donated nearly $70,000 to the campaign, and was nearly single-handedly responsible, in terms of both manpower and capital, for providing Roosevelt with the delegates of the New Jersey Republican primary. The cash flow continued after Roosevelt had moved camp to the Progressives; $111,250 was the amount Munsey gave to the new party immediately following its formation, and the support continued in following months. Munsey was also among a small group of advisers that helped decide where and when the candidate would go on the stump trail.

The extent to which Roosevelt and Munsey were personal friends is uncertain; Munsey is never mentioned in Roosevelt's 1913 Autobiography, although it is well-known that the two had met long before 1912 (on the other hand, Munsey's friendship with George Perkins, lasting decades, has been well-documented). Stories abound concerning trips the two, with others, took during the campaign, and of one incident in particular, wherein a jovial, boyish Roosevelt talked the squeamish Munsey into feeling his ribs, where a bullet had been lodged, and left, after a recent assassin's attempt to murder the candidate (this was the famous instance in which, after being shot, Roosevelt sought medical attention only after having finished the speech he had started before the assailant attacked). "Poor dear Frank" Roosevelt called Munsey quite often, either a jab at the reserved, un-warrior-like appearance and somewhat dull demeanor Munsey displayed, or perhaps even a sign of Roosevelt's appreciation for Munsey's financial support, which he drew on heavily throughout the 1912 election season. Munsey, judging from eyewitness accounts, seems to have been a member of a close-knit group of like-minded associates, and perhaps friends. Henry L. Stoddard, friend to both Munsey and Roosevelt reported in his work, As I Knew Them, that following the loss of the Republican nomination to Taft, Munsey had emotionally offered his full support to Roosevelt, in what Stoddard believed to be a heartfelt promise of friendship.

No matter the level of personal, financial, or propagandist support that Munsey offered, the election of 1912 did not go in Roosevelt's favor, with Woodrow Wilson taking advantage of the cleft in the Republican Party brought about by the Taft/Roosevelt rivalry. With Roosevelt's defeat, Munsey retreated from politics for the most part, although his dislike of Taft's successor, Woodrow Wilson, would show itself in editorials blasting the president for both a lack of nationalism, and a tendency towards cowardice: "When all this was happening [referring to the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915], accounts that wring the soul of all humanity save that of German blood, the President went off to the country for a day at golf. . . Great God! . . . Has there been such a spectacle as this since Nero fiddled at the burning of Rome?" Munsey continued his assault on Wilson, being one of the most vocal published attackers of The League of Nations proposal, and, more or less, of anything Wilson did during the Versailles Peace Conference of 1919. His outspoken dislike for Wilson's Democratic policies was so virulent that, when Republicans returned to the White House in the form of Warren G. Harding, many, including Munsey himself, assumed he would be offered a post in the new administration, Secretary of the Navy and U.S. ambassador to Great Britain being among the assumed rewards; much to Munsey's chagrin, however, no such presidential offer arrived, and his full attention returned once again to his papers.

After a terrible amount of suffering over the course of ten days, brought about by both appendicitis and related operations, Frank Andrew Munsey died on the 22nd of December, 1925 at the age of 71. His newspapers, per his orders, were all sold, and the Argosy was eventually sold to Popular Publications in 1942, sixty years after the ambitious, young telegraph operator from Maine had arrived in New York and began publishing the title that would place him among the richest entrepreneurs of his generation.

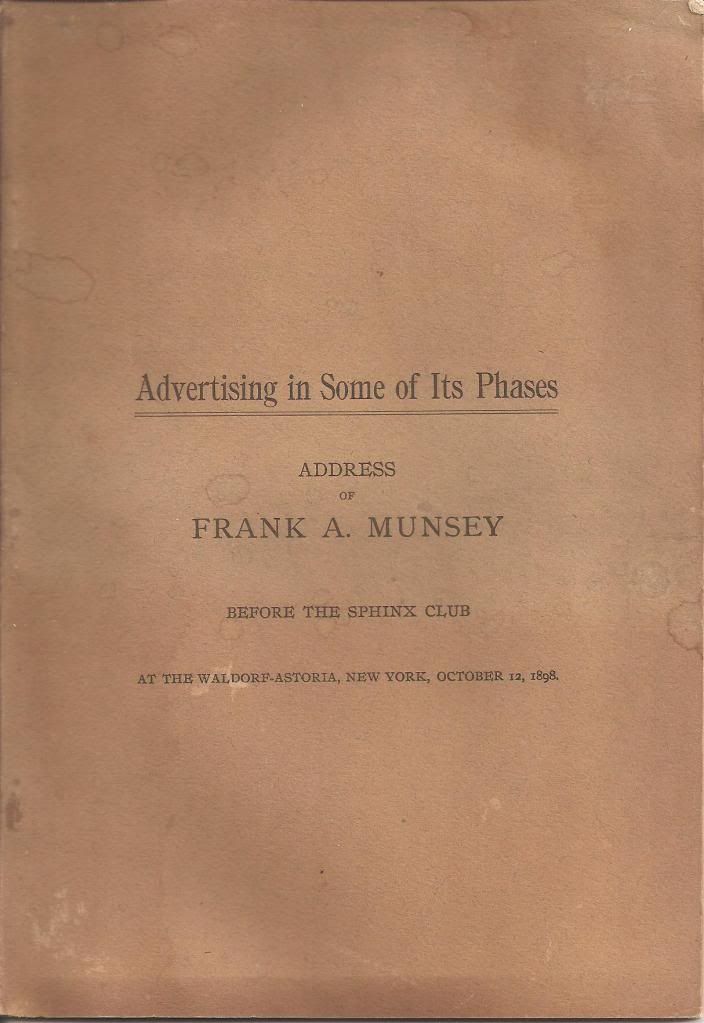

|

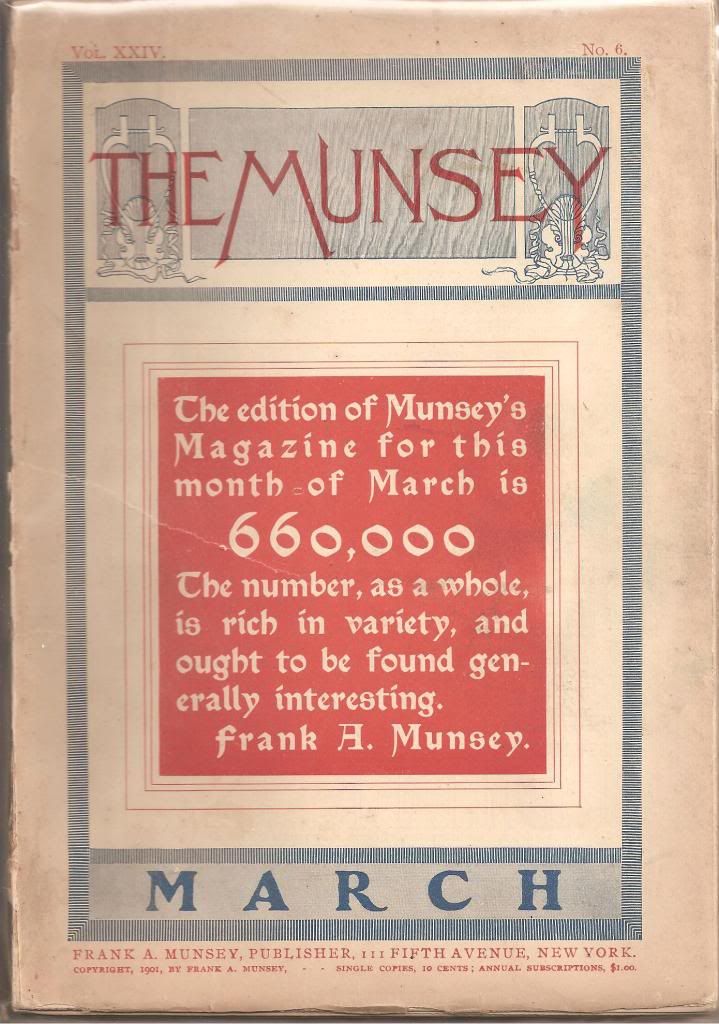

| What was probably (with issues being released at least a week prior to the cover date) the last issue of Argosy published and distributed before Munsey's death |

As always, I am sincerely grateful for your time, and I thank you.

Sources:

Britt, George. Forty Years – Forty Millions : The Career of Frank A. Munsey. Port Washington: Kennikat Press, 1972.

Stoddard, Henry L. As I Knew Them - Presidents and Politics From Grant To Coolidge. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1927.

Photographs of Frank Munsey, courtesy of George Britt's biography (Munsey in 1896), and the Library of Congress, respectively.

Thanks to Galactic Central's Pulp Magazine Cover Index for the image of Argosy 12/26/1925.

No comments:

Post a Comment