The era during which Munsey's wealth began to accumulate exponentially also heralded an unprecedented change in America itself; technology, society, philosophy: everything was in flux at the turn of the Twentieth Century. There was prosperity at home, and America was taking ever more strident steps in becoming a dominant world power, as shown by such international actions as its involvement in the quelling of the Boxer Rebellion (and subjugation, through treaties, of the Manchurian Qing dynasty) in far-off China.

During the first two decades of the century, Munsey had already made his fortune, the Alger-story of his life had been transfigured into one of opulence and, more importantly, influence. Through both his periodical and newspaper ventures, Munsey's publications ended up in the hands of millions of Americans, and the highest offices in the land came to Munsey, asking for his assistance on a variety of matters. Munsey spurned President Warren G. Harding's attempts to gain the publisher's endorsement of America's entry into the World Court, just as, years earlier, he had argued, in print, against America's joining the League of Nations following the First World War; there was "no man more effective than himself, Frank Munsey, in turning the country against Wilson and his League. . ." Munsey had attended dinners with both presidents, as well as Taft and Coolidge, neither of which he agreed with or liked very much. It was Presidents William McKinley, and more so Theodore Roosevelt, with whom Munsey was to find political and societal allies.

Munsey's appreciation of Roosevelt began years before the latter's ascension to the Presidency; Munsey had followed his career, as early as 1895, and commissioned articles praising him in many of his publications, as demonstrated by the following excerpt from an 1899 issue of The Quaker, later re-titled The Junior Munsey:

"One of the most picturesque figures of today. . . is Theodore Roosevelt. A brief outline of the positions this versatile man has held, and a mention of his accomplishments will show the ease with which he could face and overcome the wolf at the door. . . He has been a close student of law, as well as of nature. He has been a member of the New York State Legislature, the President of the Board of Police Commissioners, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Colonel of Volunteers, and fought with his famous Rough Riders on three battlefields. . . "

While Munsey and Roosevelt's political views may have been at odds in earlier years (they were on opposing sides of the bitterly contested nomination of James G. Blaine as the Republican candidate for the 1884 presidential election), Roosevelt, for the most part, received Munsey's support following the 1901 assassination of McKinley by would-be anarchist Leon Czolgosz, an event which immediately placed the Rough Rider in the Oval Office. Following two terms that saw tremendous reforms in everything from foreign policy (The Roosevelt Corollary) to domestic conservation (establishment of the United States Forest Service), Roosevelt refused to run for a third term, and placed the hopes for further continuation of his policies in the hands of his chosen successor, William Howard Taft. Taft, however, had slumped in this duty (in Roosevelt's mind), and the former president sought to usurp the Republican presidential nomination of 1912 from his former friend. Eventually losing the nomination to Taft (through what many considered to be party politics rather than the voters' choice), Roosevelt placed his candidacy with that of the newly-formed Progressive Party.

Munsey believed that Roosevelt had become a bit more conservative following his departure from the Presidency, and agreed with him on numerous issues, including, but not limited to, the establishment of a national minimum wage law and the regulation (as opposed to dismantling) of large businesses - a belief concurrent with Munsey's vision of a Carnegie-inspired "publication trust." It was, in fact, Munsey himself who was among the first to break the news of Roosevelt's joining with the Progressives:

"Mr. Roosevelt will be nominated for President by a new party. He refuses to have anything to do more with the Republican Convention now in session in this city [Chicago]. He would not now take a nomination from that body if it were given to him. He regards it as a grossly illegal organization, formed by the force of men fraudulently seated. Taft will probably be nominated late tomorrow. It is now the earnest wish of Mr. Roosevelt and his friends that the nomination go to him. They regard him as the proper nominee of such a convention."

With that statement, Munsey not only made his political stance known during what was rapidly becoming a hotly-contested and divisive election, but also became one of, if not the most important and invaluable financial resource of Roosevelt's "Bull Moose" campaign.

At the risk of running too long on posts, the conclusion of Munsey's work in politics will appear in the next post rather shortly. I have also included here the conclusion of pages, written by Munsey himself, concerning the production of his periodicals. Once again, I would like to thank you sincerely for reading, and for your time.

Sources:

Britt, George. Forty Years – Forty Millions : The Career of Frank A. Munsey. Port Washington: Kennikat Press, 1972.

Chace, James. 1912 - Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft & Debs - The Election That Changed The Country. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004, 121.

Coman, Wynn. "If These Men Were Penniless?" The Quaker (The Junior Munsey), January, 1900, 217.

Crunden, Robert M. ed. Ministers of Reform - The Progressives' Achievement in American Civilization, 1889-1920. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1985, 207.

Donald, Aida D. Lion in the White House - A Life of Theodore Roosevelt. New York: Basic Books, 2007.

Tindall, George Brown. America - A Narrative History - Volume Two. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1988.

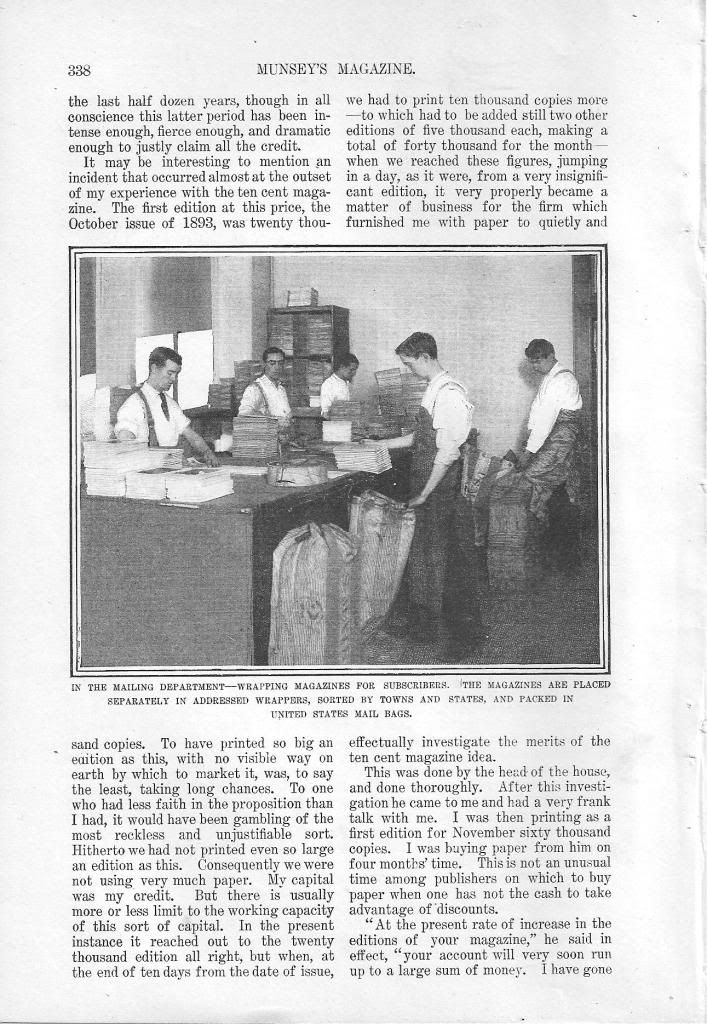

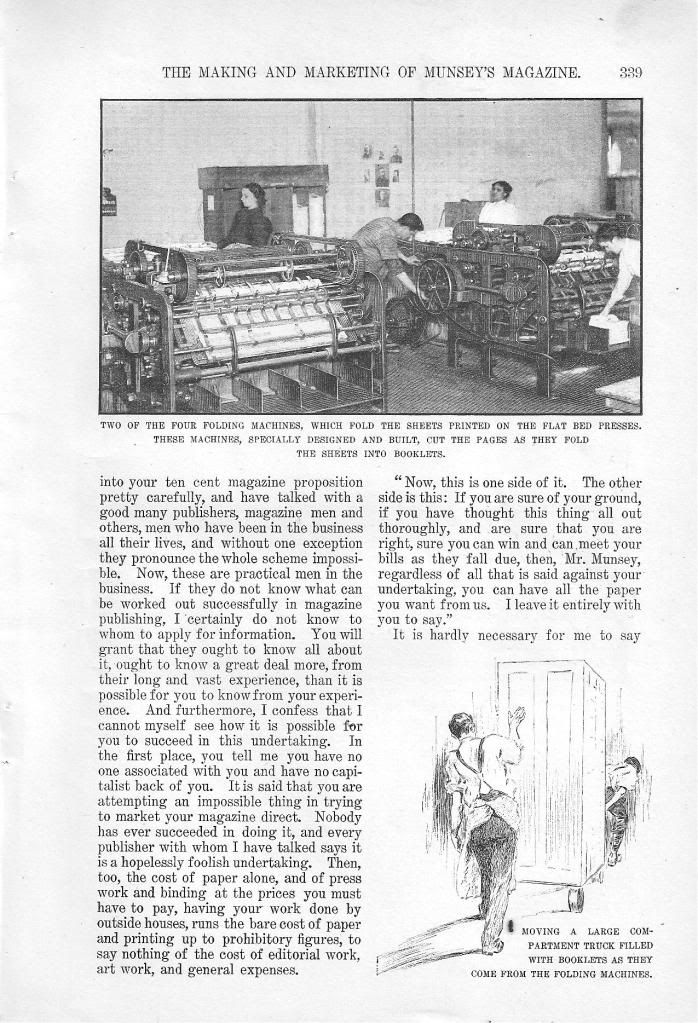

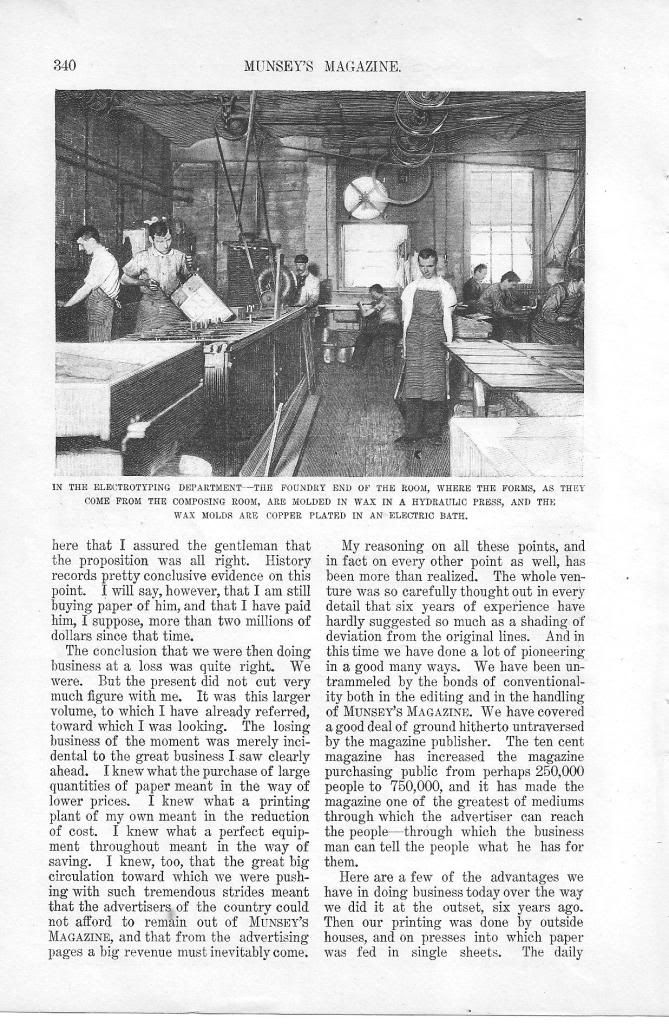

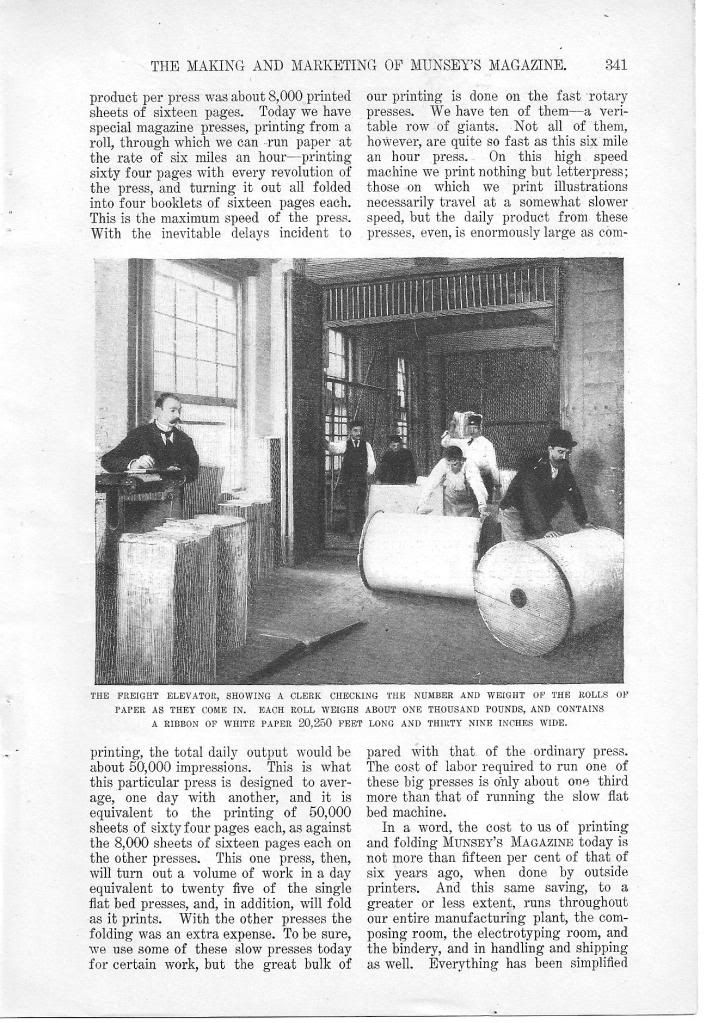

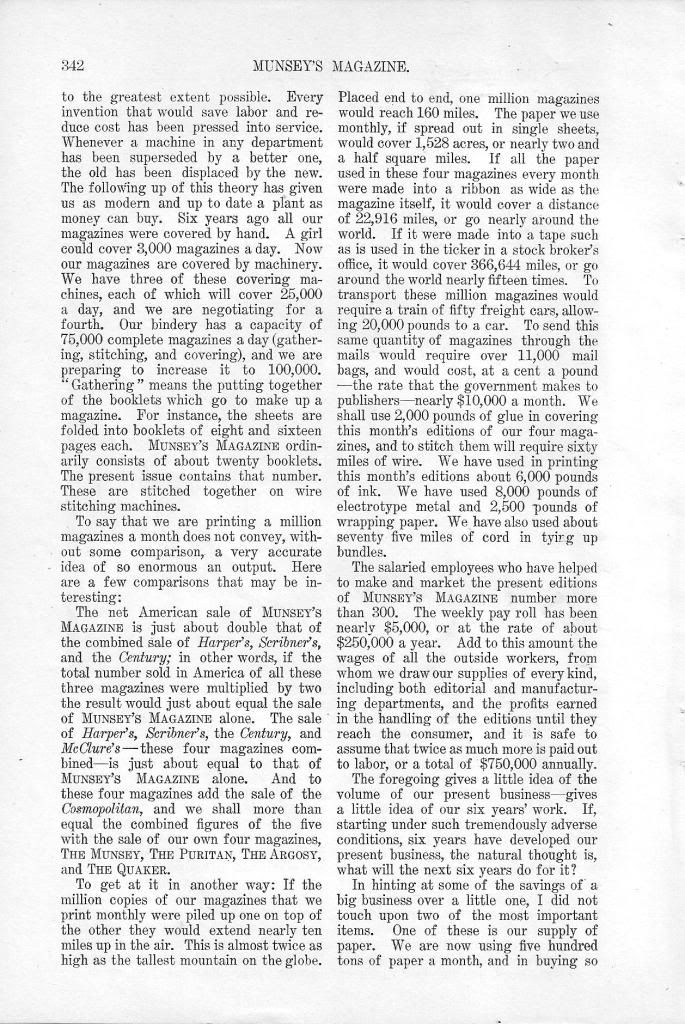

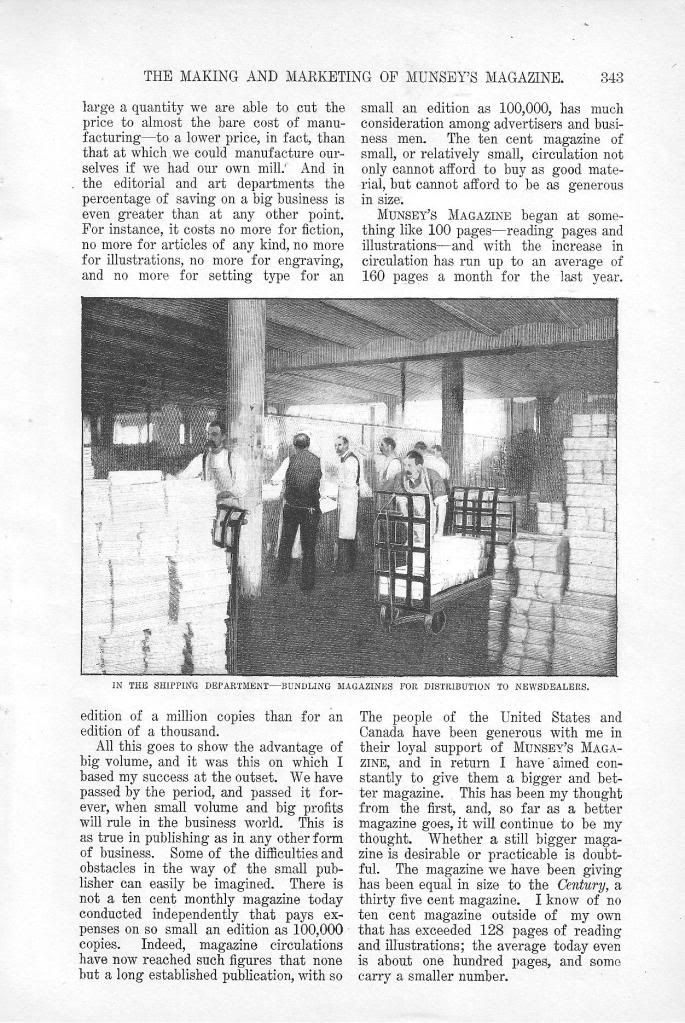

Very interesting piece on Munsey and Roosevelt. But again, the photos really catch our attention and show us fascinating details of the magazine business over 100 years ago.

ReplyDelete